Last updated on 2019-10-09

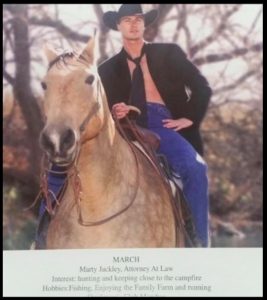

Attorney General Marty Jackley continues to use the authority of his office to support efforts to make life worse for Americans. Last week Jackley further eroded South Dakota’s good name by joining fifteen other cranky conservative states in a friend of the court brief to the U.S. Supreme Court taking the side of a Michigan funeral parlor that fired an employee for deciding he was a woman.

Attorney General Jackley and his fellow amici curiae lack a moral case for filing their brief… but they may have a technical legal case.

Anthony Stephens was a funeral director at R.G. & G.R. Harris Funeral Homes in Michigan. Stephens was born male but decided he was female, renamed himself/herself Aimee, and told her boss in July 2013 that she planned to dress appropriately to her female identity. Harris Funeral Homes fired Stephens, and Stephens, with the help of the ACLU, went to court, charging sex discrimination under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act. Stephens lost in district court but won on appeal in the U.S. Sixth Circuit.

Harris Funeral Homes has appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. A.G. Jackley and friends filed an amici curiae brief Friday urging the highest court to “hear this case of national importance.” Their argument revolves entirely around the distinct definitions of sex and gender identity:

The Sixth Circuit erred by categorically declaring “[d]iscrimination on the basis of transgender and transitioning status is necessarily discrimination on the basis of sex.” EEOC v. Harris Funeral Homes, Inc., 884 F.3d 560, 571 (6th Cir. 2018). The text, structure, and history of Title VII, however, demonstrate Congress’s unambiguous intent to prohibit invidious discrimination on the basis of “sex,” not “gender identity.” The term “gender identity” does not appear in the text of Title VII or in the regulations accompanying Title VII. In fact, “gender identity” is a wholly different concept from “sex,” and not a subset or reasonable interpretation of the term “sex” in Title VII. The meaning of the terms “sex,” on the one hand, and “gender identity,” on the other, both now and at the time Congress enacted Title VII, forecloses alternate constructions.

…The text of Title VII prohibits invidious discrimination “on the basis of sex.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a). The statute does not define “sex”; thus, the ordinary mean-ing of the word “sex” prevails. Asgrow Seed Co. v. Winterboer, 513 U.S. 179, 187 (1995) (“When terms used in a statute are undefined, we give them their ordinary meaning.”). When Congress enacted Title VII, virtually every dictionary definition of “sex” referred to physiological distinctions between females and males, particularly with respect to their reproductive functions [Douglas Peterson, Nebraska Attorney General, amici curiae brief, Harris Funeral Homes v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, submitted to U.S. Supreme Court 2018.08.24].

Peterson, Jackley, et al. distinguish sex from gender identity with dictionary definitions and the words of the very originator of the term transgender:

Early users of “gender identity”—a term first in-troduced around 1963—distinguished it from “sex” on the ground that “gender” has “psychological or cultural rather than biological connotations.” Haig, supra, at 93. “Biological sex,” they contended, is not the same as “socially assigned gender.” Id. (quoting Ethel Tobach, 41 Some Evolutionary Aspects of Human Gender, Am. J. of Orthopsychiatry 710 (1971)). While “sex” cannot be changed, “gender” (per this view) is more fluid. The 8 Federal Government on Autopilot: Delegation of Regulatory Authority to an Unaccountable Bureaucracy: Hearing Before the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 114th Cong. 13 (2016) (stmt. of Gail Heriot, Member, U.S. Comm’n on Civil Rights) (quoting Virginia Prince, Change of Sex or Gender, 10 Transvestia 53, 60 (1969)).

In 1969, Virginia Prince, who is credited with coin-ing the term “transgender,” echoed the view that “sex” and “gender” are distinct: “I, at least, know the difference between sex and gender and have simply elected to change the latter and not the former. . . . I should be termed ‘transgenderal.’ ” Id. And in the 1970s, feminist scholars joined the chorus attempting to differentiate “biological sex” from “socially assigned gender.” Haig, supra, at 93 (quoting Ethel Tobach, 41 Some Evolutionary Aspects of Human Gender, Am. J. of Orthopsychiatry 710 (1971)). Thus, at the time Congress enacted Title VII, “sex,” “gender identity,” and “transgender” had different meanings. Given all of the above, the use of the term “sex” in Title VII cannot be fairly construed to mean or include “gender identity.” The Sixth Circuit erroneously conflated these terms to redefine and broaden Title VII beyond its congressionally intended scope [amici curiae, 2018.08.24].

Jackley and friends argue that efforts since 1964 to write explicit protections gender-identity discrimination into law demonstrate that Title VII as written does not protect Aimee Stephens from being fired because of her gender identity. The amici curiae thus argue that the Sixth Circuit “not only ignored the will of Congress, but bestowed upon itself (an unelected legislature of three) the power to rewrite congressional enactments in violation of the separation of powers.”

I’ll admit, an argument about basic definitions, legislative intent, and the separation of powers sounds better than, “Transgender people creep us out, so let’s fire ’em!” But even this definitional and constitutional toehold may not support the anti-trans discrimination that Jackley wants to permit. Refer back to the Sixth Circuit’s ruling, which refers to a 1989 U.S. Supreme Court ruling that said sex discrimination can include gender identity discrimination:

In Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989), a plurality of the Supreme Court explained that Title VII’s proscription of discrimination “‘because of . . . sex’ . . . mean[s] that gender must be irrelevant to employment decisions.” Id. at 240 (emphasis in original). In enacting Title VII, the plurality reasoned, “Congress intended to strike at the entire spectrum of disparate treatment of men and women resulting from sex stereotypes.” Id. at 251 (quoting Los Angeles Dep’t of Water & Power v. Manhart, 435 U.S. 702, 707 n.13 (1978)). The Price Waterhouse plurality, along with two concurring Justices, therefore determined that a female employee who faced an adverse employment decision because she failed to “walk . . . femininely, talk . . . femininely, dress . . . femininely, wear make-up, have her hair styled, [or] wear jewelry,” could properly state a claim for sex discrimination under Title VII—even though she was not discriminated against for being a woman per se, but instead for failing to be womanly enough. See id. at 235 (plurality opinion) (quoting Hopkins v. Price Waterhouse, 618 F. Supp. 1109, 1117 (D.D.C. 1985)); id. at 259 (White, J., concurring); id. at 272 (O’Connor, J., concurring).

Based on Price Waterhouse, we determined that “discrimination based on a failure to conform to stereotypical gender norms” was no less prohibited under Title VII than discrimination based on “the biological differences between men and women.” Smith v. City of Salem, 378 F.3d 566, 573 (6th Cir. 2004). And we found no “reason to exclude Title VII coverage for non sex-stereotypical behavior simply because the person is a transsexual.” Id. at 575. Thus, in Smith, we held that a transgender plaintiff (born male) who suffered adverse employment consequences after “he began to express a more feminine appearance and manner on a regular basis” could file an employment discrimination suit under Title VII, id. at 572, because such “discrimination would not [have] occur[red] but for the victim’s sex,” id. at 574. As we reasoned in Smith, Title VII proscribes discrimination both against women who “do not wear dresses or makeup” and men who do. Id. Under any circumstances, “[s]ex stereotyping based on a person’s gender non-conforming behavior is impermissible discrimination.” Id. at 575 [Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, ruling in EEOC & Stephens v. Harris Funeral Homes, 2018.03.07].

Attorney General Jackley and friends avoid saying anything bad about transgender Americans in their brief. They focus strictly on the definitional argument. But as we know from our own debates about anti-trans legislation in South Dakota, conservative Republicans become semantic scholars only when they need to hide their true bullying intentions.

Attorney General Jackley didn’t have to lift this finger. He could have left the argument in this case to the queasy Jesus-y Michigan funeral home and its conservative allies who are eager to throw another hot-button case before the Trump court. But as in 2016 when he signed onto a Nebraska lawsuit against President Barack Obama’s guidance to schools on transgender fairness, Attorney General Jackley is happy to lend a hand when there’s a chance to give the finger to Americans who don’t conform to his Christian values.

p.s.: Harris Funeral Homes provided free suits and ties for male employees who work with the public but did not give free skirts and business jackets to its public-facing female employees. That, said the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, was clear sex discrimination.

The Supreme Court shouldn’t hear this case. It was settled in Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins, 490 U.S. 228 (1989). “Congress intended (under Title VII) to strike at the ENTIRE spectrum of disparate treatment of men and women resulting from sex stereotypes.”

Will there be a similar ask to respect standing legislation and legislative process when the Supreemes consider a national ban on abortion? This gang of AGs did not ask for legislative deference when a national Right to Work was written into the First Amendment for public employees by this court.

Executive branch stuarts ought to enforce the laws on the books.

Adding gender identity to federal anti-discrimination laws is for Congress to do, not for the courts to do through interpreting something in that’s not there. I believe Jackley’s legal position is correct here. But there is no reason for SD to stick its nose into this.

I tend to agree with Rorshach that on its face the law does not seem to precude discrimination based gender identity due to the apparent omission of the term “gender.” The problem with that view, however, is that, according the the 6th Circuit, a plurality of the SCOTUS in Price (as Porter points out) has considered the intent of the statute to prohibit discrimination based on sexual stereotypes, including the manner in which an individual dresses. Thus, stereotyping an individual simply because of his or her gender identification does run contrary to the intent of the law to prohibit discrimination based on sexual stereotypes.

The question raised is whether the current Justices of the SCOTUS desire to overrule the plurality opinions in Price, or let stand the plurality language indicating that discrimination due to sexual stereotyping based on failure to live or dress as typical men or women is unlawful under existing law.

That said, I also agree with Rorschah that the Attorney General’s office or legislature of State of SD has no business whatsover wasting SD taxpayer money trying to convince the SCOTUS to rule one way or another on the issue. If the issue is important to the majority of people in our State, then our elected federal representatives simply need to propose legislation to clarify whether businesses and public entities are authorized to discriminate against individuals based on stereotypes about how the majority thinks our inhabitants all should dress or medically (hormonally) treat their particular private parts.

Then this strict text over context should also mean that the Second Amendment’s right to bear “arms” does not extend to ammunition? We can ban all the things that are needed to make the arms work? Certainly bumpstocks are not “arms?

It’s not only about trans people. If a business can fire an employee for not dressing according to sexual stereotype, then who determines the stereotype?

On the other hand, if SCOTUS upholds the ruling, straight men can wear skirts or kilts and blouses. Not that they necessarily would, but . . .

I don’t think companies should have the power to decide how women and men should dress according to gender. What an enormous can of worms that would open!

BTW, schools that require uniforms should not be able to force girls to wear skirts. Students should have the option of slacks or skirts.

O, I wondered about that: as with “arms”, can we find other terms that meant something very different and more limited when the Constitution or related legislation was enacted but which have been redefined in practice and by the courts without legislative amendment? Can “transgender” become part of “sex” in the same way that “automatic rifles” become part of “arms”? Other examples?

I like the legal perspective Ror and BCB bring. Practically, the South Dakota AG doesn’t need to lift a finger to see that this case is handled appropriately. As BCB notes, AG Jackley is doing applying our heft to get the Trump court to overturn past court precedent… as we did to get SCOTUS to overturn Quill and let us increase our sales tax revenues. Should South Dakota really be working that hard to get the court to abandon stare decisis?

Curious: just how firm is the Price Waterhouse precedent? Is it as firm as Quill was?

Jackley, all heady after SD’s recent SCOTUS ruling allowing internet taxation , seems to want SD to buy him more notoriety before his term in office ends forcing him out into the cold cruel world.