Harvard researchers are developing a new, faster way to gauge America’s economic activity amidst the coronavirus pandemic. The Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker (OI) uses near-real-time data from credit card processors, payroll firms, and other private companies to measure mow much we are working, earning, and spending. OI data are about a month ahead of the government’s current survey-based statistics.

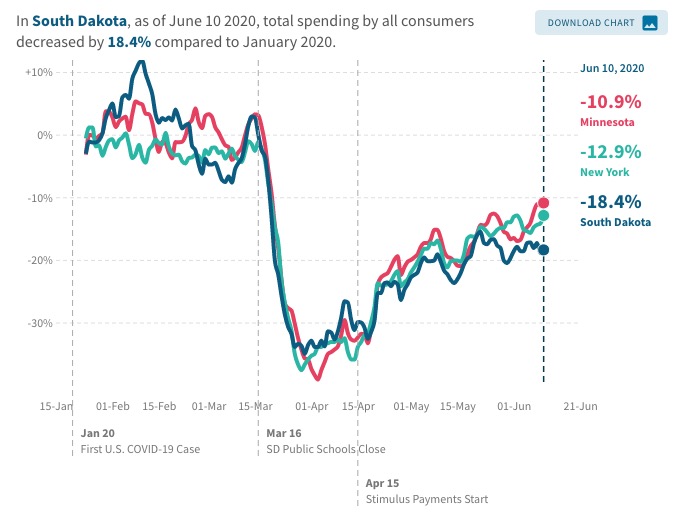

According to OI, South Dakota’s consumers have pulled back more than South Dakota’s employers relative to other states. Compared to January 2020, consumer spending in South Dakota as of June 10 was down 18.4%. That’s the fifth-largest drop in the country, behind only Oregon, California, Rhode Island, and Washington, D.C. Minnesota and New York issued much stiffer coronavirus stay-home orders than our state did, yet their residents decreased their spending less than South Dakotans did:

One of the few economic bright spots nationwide is grocery spending, which spiked over 60% mid-March when we all went into bunker-stocking mode and remains up 8.9% as more people cook and eat at home. But OI’s data shows South Dakota is one of only three places (the other two: Rhode Island and Iowa) where grocery sales are down since January:

South Dakota bucks one other important national trend. In general, lower-income Americans have responded to the April stimulus and brought their spending closer to pre-pandemic/pre-recession levels than have middle- and upper-income Americans. All three groups pulled back on spending 30% or more as of April 1, but as of June 10, lower-income Americans’ spending has bounced back to just 4.0% below January’s level; middle-income spending remains down 9.9%; and upper-income folks are still dragging at 16.8% under January spending.

Here in South Dakota, everyone’s spending dropped 35% in early April, comparable to the national recession. But by income group, our spending recovery trend is reversed: higher-income spending has recovered to within 15.0% of January’s level while middle-income spending remains down 17.5% and lower-income spending remains down 27.3%. Either the feds have done a crappier job of getting stimulus checks out to lower-income South Dakotans or the South Dakotans winning the least bread are more frugal and/or pessimistic amidst pandemic.

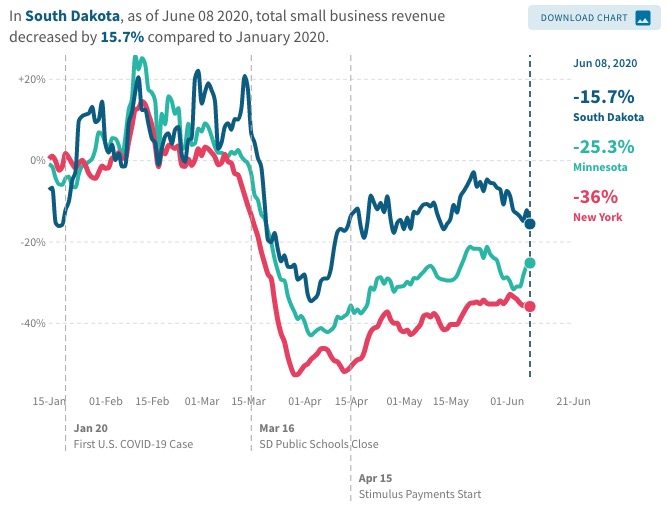

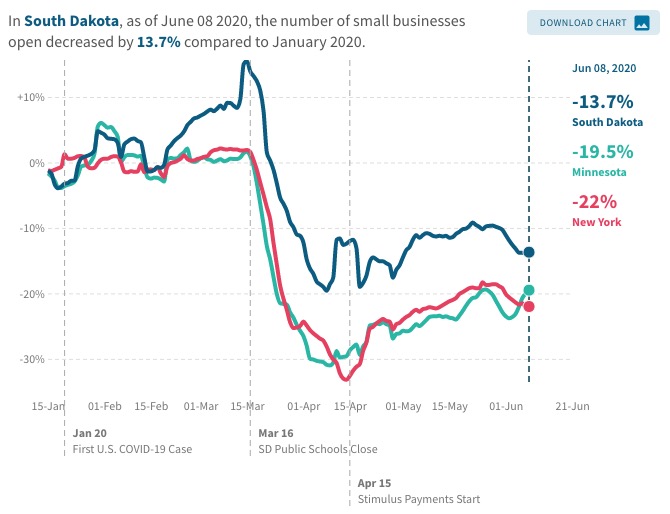

Flip to business stats, and South Dakota is doing better than the U.S. as a whole. Small business revenue is down 19.1% nationwide but down only 15.7% in South Dakota. The number of small businesses open dropped 16.9% nationwide but only 13.7% in South Dakota. And we beat Minnesota and New York in both of those categories:

South Dakota is a small counterexample to the national support for the idea that stimulus policies have the greatest impact when they target lower-income people. In this pandemic, we see lower-income Americans injecting their stimulus payments right back into the economy while upper-income Americans hold back.

Dylan Matthews of Vox notes that the OI data also indicate that, in this uniquely disease-driven recession, the stimulus helped consumers but not small businesses:

…the authors find little effect of the stimulus on small business revenues, and absolutely no effect on small business employment. Small businesses tend disproportionately to sell goods and services in-person, and a disproportionate share of their revenue comes from wealthy people. So the stimulus, which was both less meaningful for wealthy people and came at a time when people were understandably afraid to leave their homes, did little to help them [Dylan Matthews, “A New Paper Finds Stimulus Checks, Small Business Aid, and ‘Reopening’ Can’t Rescue the Economy,” Vox, 2020.06.17].

Matthews that the OI researchers find the Paycheck Protection Plan does not appear to have preserved jobs, as firms with fewer than 500 employees still reduced work hours nearly as much as firms with 1,500 employees, which were too big to qualify for PPP.

The OI researchers also find that economic activity is driven by consumer confidence in public health measures more than by any “reopening” declaration by elected leaders:

First the authors compared Minnesota (which did an early partial reopening on April 27) to Wisconsin (which did so on May 13 in response to a court order). As you can see, despite very different reopening timing, the trajectories of the two states was nearly identical when it comes to consumer spending, and the orders themselves didn’t seem to do much.

Then the authors expanded this analysis to a total of 20 states that issued reopening orders prior to May 4; for each reopening date, they paired these states with control states that didn’t reopen, and that prior to reopening had a similar trajectory in employment or consumer spending. The authors find that consumer spending was growing before formal reopening and kept growing after; it’s possible the reopening caused some of the boost. But in any case, employment did not rise at all in the reopened states.

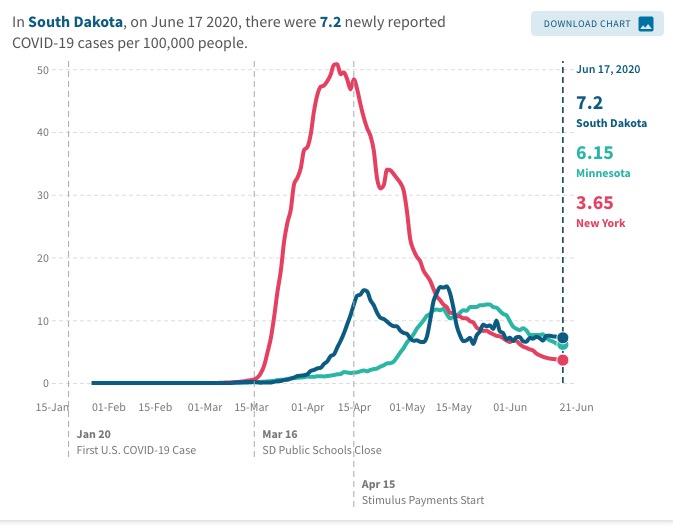

“The implication of this finding is that restoring confidence in public health may be a prerequisite to a full recovery,” the authors conclude. That was true in 1919 during the Spanish flu, and it seems to be true again today [Matthews, 2020.06.17].

One more note about the pandemic driving all of these numbers: as of June 17, South Dakota’s rate of newly reported coronavirus cases was 7.2 per 100,000. The national rate was 7.1.

There is quite a bit of discussion amongst Minnesota and Wisconsin public and private experts on why our results have varied despite our different responses. There is no consensus answer, but lots of theories.

There’s a lot to study in this pandemic and recession, Debbo. Attentive scholars and policymakers have lots of evidence to gather, analyze, and apply to future policymaking.