Two really funny things happened yesterday with regards to the South Dakota Republican Party’s effort to restrict your initiative and referendum rights.

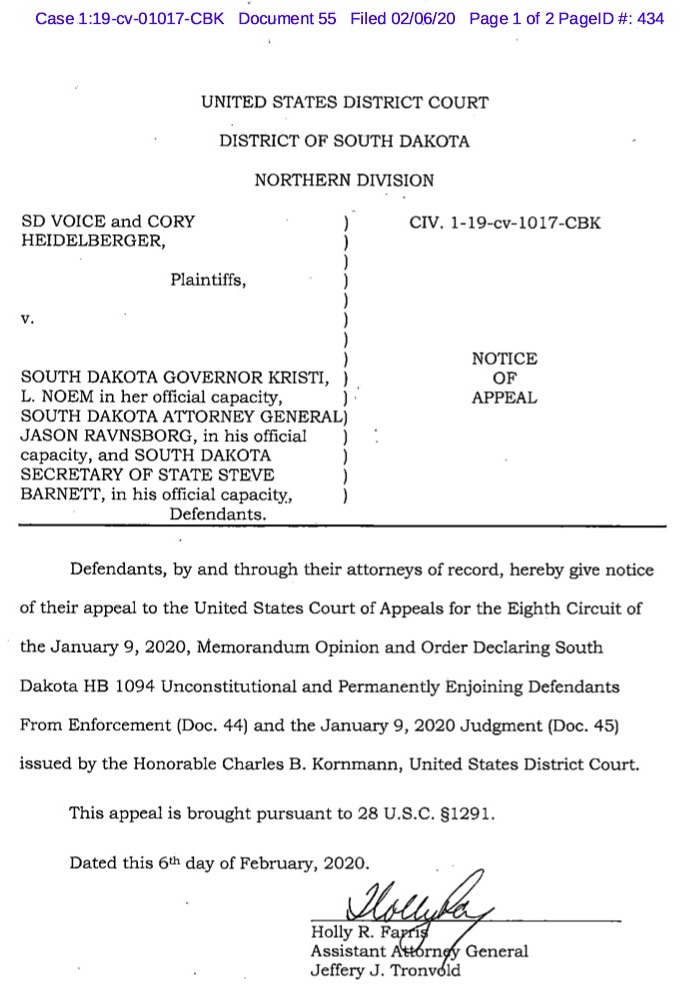

First, the Attorney General’s office notified the U.S. District Court of South Dakota that intends to appeal Judge Charles Kornmann’s ruling against 2019 HB 1094, the unconstitutional circulator registry and badging law, to the Eighth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals:

The state did not appeal its loss last year in SD Voice v. Noem I, in which Judge Kornmann overturned Initiated Measure 24, the unconstitutional ban on out-of-state contributions to ballot question campaigns. Either Attorney General Jason Ravsnborg is more keenly interested in defending the Legislature’s bad ideas than in fighting to protect measures approved by the general electorate, or Ravnsborg is willing to stand my dunking on him in court once but not twice.

But on the same day, two Republican legislators filed a bill that may moot the appeal. Senator Jim Stalzer (R-11/Sioux Falls) and Representative Jon Hansen (R-25/Dell Rapids), the guy who made the state’s second loss in court possible by writing 2019 HB 1094, have filed Senate Bill 180, a revised version of last year’s circulator registry and badging bill.

SB 180 does the same things as HB 1094: it requires people circulating ballot question petitions to register with the Secretary of State before circulating; surrender their name, physical address, phone number, e-mail address, and other personal information to a public database; and wear a badge with a personally identifying identification number any time they circulate their petitions.

But this year’s bill has two key differences:

- SB 180 abandons the broad HB 1094 definition of “circulator” that criminalized speaking out in favor of a ballot measure petition drive without registering. That definition, which mentioned “soliciting” signatures, was a key part of Judge Kornmann’s ruling against HB 1094. SB 180 attempts to narrow the definition of “solicit” to include only individuals in the physical presence of a circulator with petitions in hand.

- SB 180 applies all of its restrictions solely to paid circulators. SB 180 imposes no new burdens on volunteer circulators.

Stalzer and Hansen are still committing the content discrimination Judge Kornmann found in last year’s circulator registry and badging. SB 180 imposes burdens on people advocating ballot measures, but it imposes no burdens on people paid to oppose and sabotage the circulation of ballot measures, like the professional petition blockers hired by payday lenders in 2015 to harass circulators like Miller Cannizzaro and stop them from getting signatures on the 36% payday loan rate cap. If there is any problem in South Dakota’s initiative and referendum petition process, it is the interference of paid thugs like those who fight to prevent South Dakotans from signing petitions and voting. SB 180 ignores that very real problem and continues the ruling party’s discrimination against citizens promoting the vital check and balance of ballot measures on the Legislature.

But Senate Bill 180 agrees with Judge Kornmann’s ruling that last year’s measure went too far in restricting the core political speech of grassroots South Dakotans. SB 180 agrees that volunteers should not have to register or pay a fee or wear a badge to participate in a petition drive. SB 180 agrees that the circulator affidavit, added to the process in 2018, is unnecessary paperwork: SB 180 repeals that affidavit, just as Senator Reynold Nesiba’s SB 112 would do.

If the Legislature passes SB 180, it writes a substantially new version of the law that Judge Kornmann overturned and that the Attorney General wants to reinstate through appeal. By the time this appeal works through the courts (it could easily take over a year), petitioners could already be in the field for the 2022 election cycle, circulating petitions under SB 180’s regime of registry and badging for paid circulators but not for volunteer circulators. Trying to patch the overbroad requirements of 2019 HB 1094 onto the revisions made by 2020 SB 180 would be a mess.

If the A.G., Stalzer, and Hansen are coordinating their efforts at all, perhaps they think they can pursue a both-and strategy: get some form of a circulator registry and badging system back into effect, at least for paid circulators (who played a big role in getting the two marijuana measures on the 2020 ballot), then throw the dice in court to see if they can persuade a panel of judges to expand those burdens to all circulators, paid or volunteer.

But Judge Kornmann’s ruling on 2019 HB 1094 was pretty clear and well-grounded in case law. Making citizens pre-register with the state and wear ID badges to engage in political speech violates the First Amendment. Rep. Hansen appears to have read the ruling and recognized that case law with SB 180.

The state will lose its appeal and lose more money on it; the state should cut its losses, let SB 180 run its course… and then prepare for the big-money petition professionals to take that restriction to court.

Much as I think paid circulators are bad, SB 180 goes about it all wrong. What’s so hard about providing a service to encourage voluntary circulation of petitions? Isn’t that what they want, or is it just to once again find some way to screw with South Dakota citizens’ Constitutional rights?

The solution is to let the marketplace work to the advantage of un-paid circulation. Amend SB 180 to make badging available on a voluntary basis as part of an overhaul of the initiative and referendum process.

As part of this overhaul I’d like to see voluntary badging, which has the advantage of being constitutional. Have two badges available: one for in-state, un-paid circulators and one for paid circulators. Have the badges available to anyone who signs up and wants one, but don’t make it a requirement, which would violate the constitutional right to petition for redress of grievances.

The practical outcome of this would be that in-state, un-paid circulators with a badge would be the gold-standard. South Dakota residents would seek those folks out, rather than sign with someone who didn’t have a volunteer circulator badge. There would be marketplace pressure for sponsors to work in a more grassroots way with South Dakota citizens, rather than rely on big money efforts with paid circulation.

This should be part of a complete reform of the process, however. Most of the current pre-petitioning bureaucracy is unnecessary and needs to be repealed in order to get back to what the initiative and referendum was meant to be, not what special interests have twisted it into. All of those repeals should be hoghoused into SB 180.

Here is a bit of SD history based on my personal recollection (which is always open to examination, correction and revision where appropriate).

In the 1980’s Governor Janklow decided SD’s poor got a little too much federal financial assistance and tried to redirect federal funds allocated to one such program to middle class voters, despite the fact that Congress had explicitly targeted the help to poorest of the poor. The program was called LIEAP for Low Income Energy Assistance Program and was implemented and administered by the SD Department of Social Services (DSS). A group of low income folks excluded from LIEAP brought a federal class action seeking a declaratory judgment and injunction against Janklow’s machinations. The federal court ruled for the impoverished plaintiff class and the State lost it’s appeal and was ordered to pay plaintiff’s attorneys fees.

As in HB 1094, the Janklow administration tried again to accomplish the same result the following year by rewriting the exclusionary rules. Another class of indigents sued, with the trial held in the Pierre federal courthouse, Judge Donald Porter presiding, the very same Judge who had ruled that the earlier implementation of the program violated federal law and issued the injunction. Much of the statistical testimony was rather dry and it seemed the Judge may have been about to nod off. On his driect examination the head of DSS, James Ellenbecker, explained in detail the changes in the language implementing the program.

On cross-examination, plaintiff’s counsel asked Ellenbecker if the State had merely “changed the language” of the exclusion to get around the initial injunction in an effort to accomplish the same result. When Ellenbecker answered affirmatively the Judge sat up, became quite interested and questioned Ellenbecker further about this tactic.

The Judge then issued a second injunction ruling that “changing the wording” did not change the nature of his earlier ruling. He had ruled that the substance of the exclusion violated federal law, not the manner in which it was written. Changing the wording to accomplish essentially the identical result got the State nowhere. The State appealed again, lost and again had to pay out thousands of dollars in attorneys fees and costs to plaintiff’s counsel.

As the tune “Where Have all the Flowers Gone” asks, “When will we ever learn?”

It used to be so much easier to control the voters before that kid from Madison showed up on the internet. – SDGOP

Don said, “What’s so hard about providing a service to encourage voluntary circulation of petitions? Isn’t that what they want, or is it just to once again find some way to screw with South Dakota citizens’ Constitutional rights?”

Well, we are talking about the SDGOP. The latter, of course.

I knew Mr. Ellenbecker as he was my boss back in the day. He was one of the most honest and honorable persons I knew at DSS. Thanks for the memory Mr. Pay

Donald, would the SB 180 paid badges help establish the same gold standard in reverse: folks with badges are the paid mercenaries who probably care less about the issue than the unbadged volunteers?

Does the application of the badges strictly to paid circulators raise any new constitutional question? In our lawsuit overturning HB 1094’s badges for everyone, the court affirmed that requiring circulators to surrender their names on the street creates a real danger of harassment and violates circulators’ right to anonymity. But does taking pay for circulation affect that right? Does taking pay implicate a new state interest in campaign finance disclosure that could cause a court to weigh the issue differently?

BCB offers a great example of comparable machinations from the Janklow era. But in the case, the wording change from 2019 HB 1094 to 2020 SB 180 does not accomplish exactly the same result. SB 180 targets a very small subset of circulators (in my petition drives last year, I had over 200 circulators, maybe only 3% of whom were paid). They are burdened in the same way paid lobbyists are burdened. If we can require paid lobbyists to register and wear badges, can we impose the same requirement on paid petition circulators?

Note that, like 2019 HB 1094, 2020 SB 180 applies only to ballot question petition circulators. If we can apply the paid lobbyist standard to paid circulators, why not apply that standard to petitioners working for candidates and make them register and badge as well?

“the paid mercenaries who probably care less about the issue” … What good is any issue if it’s not presented to the people to vote on? At that point it’s just pillow talk. Petition gatherers need little more than a proper sales technique and a thumbnail knowledge of the subject. Too much talking means you’re in the wrong place with too few possible signers.

The paid mercenaries care less about educating voters about the issue and more about boosting their paychecks with high-pressure manipulation techniques. I much prefer engaging with volunteers than with paid circulators.

But the legal question remains: is there some aspect of the paid subset that renders restrictions on their First Amendment activities subject to a different legal standard from that which overturned HB 1094’s blanket registry and badging rule?

That’s over generalization about individuals you’ve never met. I can speak from personal knowledge that the most ethical and most empathetic petition gatherers avoid South Dakota, thus you’ve not experienced their skills.

It’s a case of country mouse and city mouse.

While, as Cory make clear, the differences between 2019 HB 1094 and 2020 SB 180 may be controlling, the viability of any challenge to SB 180 would seem to depend on what was at the heart of Kornmann’s ruling on HB 1094 (and whether Kornmann’s conclusions are upheld on appeal).

If Kornmann was more concerned with the procedural overreach of HB 1094 than the procedural discrimination against people paid to advocate ballot measures in contrast to “people paid to oppose and sabotage the circulation of ballot measures,” then a successful challenge to SB 180 seems unlikely. If the opposite is true then we may just have another mere language change that results in the same 1st Amendment violations.

Incidently, this doesn’t seem to be a “content” based difference in treatment, which substantially weakens any 1st Amendment challenge. Under either HB 1094 or SB 180 the substantive “content” of the proposed intiative or proposed legislative bill appears irrelevant. Rather the distinction seems to be whether someone is paid to present to proposal, whatever the content, to voters or to stop it. The lack of a “content” problem may well be the key factor if either HB 1094 or SB 180 survives judical scrutiny.

Do I correctly understand, however, that Cory’s group does not plan on challenging SB 180 if it becomes law, even if he prevails in the appellate court in the HB 1094 litigation?

First, I don’t think you can constitutionally mandate badges based on the initiative or referendum. Candidates also use circulators. No difference in what they do. It better be all of them or none of them, or they are going to have trouble in the courts.

Second, I don’t think you can single out paid circulators constitutionally for a badge requirement, though I wish you could. However, the state can provide services to residents, who wish to use them on a voluntary basis. No one has to wear a badge, but if they want to, why not? I would want to. I think it provides some added clarity for people you approach to sign. I wouldn’t make people wear three badges for three separate petitions, though. That’s nonsense. One is enough to identify you.

Third, harassment of circulators can be dealt with by a statute, similar to the prohibition of harassment against voters.

Fourth, and most important, get rid of most of the bureaucratic nonsense.

Badges. We’re On It. 😎 Some states require circulators to wear an actual badge, while other states require them to include the identifying information on the petition itself. Such laws are also known as “scarlet letter laws.” Of the 26 initiative and referendum states, seven states have such requirements. One, Colorado, requires circulators to wear a badge. The other six require the notice to appear on the petition form. Two states—Michigan and South Dakota—passed such requirements in 2018.

Hi Cory,

Picky linguistic point.

I don’t think that’s the proper way to use moot as a verb. My understanding is that it means “to raise something for discussion”, not “make impotent”.

Kind regards,

David

Cory’s use of “moot” is correct in the legal sense.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/constitution-conan/article-3/section-2/clause-1/mootness

If the bill Cory references becomes law, that indeed constitutes a change in law that could “moot” the appeal.

I am confused with SBs 102, 112 and 180 and whether Hansen and Ravnsborg are abusing process, as Debbo points out The Borg are wont to do. Moot you.

Hi BearCreek!

My understanding of moot is that as a noun, it refers to a place where a debate is being held. A council. It used to be for real councils, but nowadays mostly refers to mock trials like those in law school.

As an adjective, when moot is applied to a legal position, it thus takes on the connotation that this policy isn’t going to affect anyone, the discussion is for (classroom) debate only. Here I completely agree with you and Cornell that a case can “become moot” when it no longer affects anyone.

But as a verb it hearkens back to the noun version. To moot means to raise a subject up for discussion. “I moot that we go to Sushi Masa for dinner.” And if we said “The prospect of going to Sushi Masa has been mooted” we should understand that a debate about eating out has begun, and not that Sushi Masa was somehow removed from the list of places where real people eat.

So the simplest fix to his sentence would be: “But on the same day, two Republican legislators filed a bill that may make the appeal moot.”

Kind regards,

David

No, Porter, it’s a statement about the ones I have met. Your comment seems to support what I’m saying: the ethical and issues-oriented professionals stay away, and the ones who come to our state are mercenaries out to do anything for a buck.

Bear, may I contend that the content discrimination remains? SB 180, like HB 1094, imposes burdens on content that supports ballot measures while not imposing similar burdens on content that opposes ballot measures or content that supports candidates. SB 180 hinders the speech of those who advocate a process that checks Legislative power while leaving unfettered those who advocate the status quo of Legislative control.

Bear, on potential challenges to SB 180, I have not made any decision. Deciding whether SB 180 should be challenged hinges first on determining whether SB 180’s restrictions on paid ballot question petition circulators violates the Constitution. That’s what we’re all trying to figure out here.

From a constitutional perspective, it is clear (as affirmed in Judge Kornmann’s ruling against HB 1094) that the state cannot require petitioners to identify themselves before or during the act of circulating. Circulators have a right to anonymity. Neither the badge, the petition, nor the circulator handouts may include identifying information about the circulator while the circulator is circulating. (Note: SB 180 strikes the circulator’s info from the state’s mandated circulator handout, too!) So if paid/volunteer status makes no difference, SB 180’s registry and badging are still unconstitutional and will fail in court.

But we make paid lobbyists register and wear name badges to engage in core political speech that the rest of us get to do for free and without registration or badges. Have the lobbyists and their employers ever taken that badge requirement to court? What constitutional standard allows us to treat paid lobbyists and citizen speakers differently in the Legislative setting?

David, interesting semantic point! Indeed, moot as a verb originally meant to bring up for discussion. Merriam-Webster offers this word history, which fits the additional information both you and BCB provide:

It seems odd that the adjective form of a word would evolve in meaning but that its verb form would not follow suit. When I studied Russian linguistics, one of my professors said that adjectives are really verbs or derivatives of verbs… so in that professor’s world, an adjective peeling off to its own semantic field without a verb to drive it would be quite odd.

I must also admit that I have never heard anyone use moot in the verb form that David proposes. That doesn’t mean that no one ever uses it that way; it just means that I’ve never encountered that use. My lack of comprehensive reading and universal erudition proves nothing… but I invite readers to submit documented examples of moot used in comtemporary language to mean “raise for discussion” rather than “render merely academic or irrelevant”.

Allowing the use of moot as a verb meaning “to deprive of practical significance; to make abstract or purely academic” offers two advantages:

1. Brevity: my “moot the appeal” is one word shorter than David’s “make the appeal moot.”

2. E-Prime: While not a perfect example, comparing David’s structure to mine reveals that relying solely on the adjectival form to describe mootness mires us in state-of-being/becoming language. Allowing the verbal moot allows us to create more active sentences with a more specific action verb.

It seems its time for Don’s “overhaul of the initiative and referendum process…[from, inter alia]…interference of paid thugs like those who fight to prevent South Dakotans from signing petitions and voting.”

Doesn’t LRC review legislative drafts for constitutionality?

I see no difference in the level of self enrichment between paid petition gatherers and you, Cory. At the lofty level you and them are both are out to promote the Democrat progressive position. At the base level, paid gatherers are doing it for money and you are doing it to become popular so you’ll be elected to “The Club”. No difference in motivation from my view. Both motivations are some form of personal amelioration.

Cory, I tend to agree with your analysis of moot, especially when we consider the evolving nature of language itself. It is interesting to note that one popular on line Spanish teachers takes a simimilar position as your Russian Professor.

A teacher named Jordan, who calls hinself the Spanish Dude, argues there are only 6 parts of speech, but that each part really falls into a noun or a verb. For example adjectives simply expand nouns and adverbs expand verbs. This discussion starts at about 2:50 of this video:

https://spanishdude.com/quickies/parts-of-speech/

Another point that has been made by many language instructors is that language is intended to communicate an abstract idea, not a concrete word definition. Like you, I have only heard moot used as either a verb or noun in the sense that you used it, regardless of any contrary concrete dictionary definition.

The point David raises, however, is interesting and helps one gain insight to what we expect and need out of any language.

Cory, as for your “content” argument, if it is accepted by a court then the court must more carefully scrutinize the new law pursuant to 1st Amendment jurisprudence. I tend to see “content,” however, as referencing the subject matter of speech rather than a position on that subject matter. A court could easily disagree with this viewpoint.

As for your question:

There is an interesting 1995 William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal law review note that discusses the history of lobbiest 1st amendment litigation:

https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1495&context=wmborj

It discusses the case law existing as of the date of the article’s research. I have offered a lengthy edited quote from the article that provides some direction in answering your question. The article is worth reading in its entirety and updating the case law cited.

Hope this helps your analysis of SB 180!

Hi Cory!

Thanks for tracking down that interesting etymology. Obviously, I had not heard moot, the verb, used the way you used it, which is why I started this moot of moots in the first place. And we all noticed that Merriam Webster explicitly confirms my point of view:

It feels good to win an argument on the internet. Écrasez l’infâme.

Of course, language evolves and maybe we are here witnessing the birth of a future third definition. (Imagine the gangster cred we’d have from being an official entry in an etymology dictionary!) Furthermore, there was no doubt as to what your original sentence meant. From Wittgenstein’s standpoint your sentence was always correct. But that’s not you. You’ve long established your prescriptivist worldview by daily adhering to the conservative, traditional, antiquated, anachronistic salutatory direct address comma. :)

Kind regards,

David

To me, it’s simple. The SD Constitution says that if more than 5% of registered voters in SD sign a document to put a law on the ballot, it goes on the ballot. If more than 10% of registered voters do so for a constitutional amendment, on the ballot it goes. It’s up to registered voters whether they sign it or not. But that has not been the case, in a number of recent petition efforts. Instead, perfectly good, proven signatures have been thrown out for one speed bump or another. It shouldn’t matter that it’s a dog holding the petition. Or, God forbid, a cat. What DOES matter, is whether or not the signatures are truly those of registered South Dakota voters. This is assured by a sworn signature (or paw print) by the circulator on each petition form. Cheating is perjury, a FELONY. That’s all we need. The rest is NONSENSE, jammed through by a single-party Legislature grasping to maintain control, and avoid legislation that THE PEOPLE WANT, whether they like it or not.

What Polyglut so eloquently stated.

👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏👏

Porter, you are mistaken. I do not circulate petitions for self-enrichment of any form. I am certainly not doing it in order to win candidate elections. I recognize (and the evidence in South Dakota supports) that promoting ballot measures offers no synergy for boosting candidate campaigns in South Dakota.

What a line of BS, Heidelberger. I suppose you just do it because you have no choice? Even Abe Lincoln and George Washington didn’t serve for nothing. As I stated. On the lofty side people serve to promote Democrat Party ideals. You’re a member of the party, thus you do it to help yourself, in part. On the base level, getting publicity from doing good things (like petitions) helps your future candidacy, whether you choose to accept it or not.