Last updated on 2020-06-03

Aberdeen city attorney Ron Wager does me the courtesy of replying to my concern that Mayor Travis Schaunaman is violating the City Charter again by replying in our local paper that the mayor is free to circulate all the city council candidate petitions he wants. To my spotlighting of City Charter Section 7.02(a)(5)—”…no city employee shall knowingly or willfully participate in any aspect of any political campaign on behalf of or opposition to any candidate for city office….,” attorney Wager responds not with firm legal precedent but with his interpretation that taking a city paycheck doesn’t make one an employee of the city:

City Attorney Ron Wager said the key words in that prohibition is “city employee,” which, based on his interpretation, does not include elected officials like the mayor and members of the council. If it did, he said, that prohibition would mean city councilors couldn’t even participate in their own campaigns.

“My position is that he is not an employee,” Wager said of Schaunaman. “They receive a paycheck, but that’s not because they’re an employee.”

The mayor and city council are paid as elected officials, he said [Elisa Sand, “Councilors, Mayor Can Circulate Petitions for Others,” Aberdeen American News, 2020.04.15].

The City Charter uses the terms “official” and “employee” side by side in numerous places, but it offers no explicit definition of either. Normally, absent a definition, the courts take terms at their commonly understood meaning. Members of the City Council, including the mayor, “work for the city” in the most literal sense: they are hired by the voters to work for the entire city. They get paid for that work. They have clear job descriptions in the City Charter. Wager just reaches for an alternate term, elected officials, but offers no standard rooted in the language of the law.

To support his interpretation, Wager appeals to the intent behind the law but then reads the law wrong himself:

As the provisions are written the goal is to prevent city employees from being pressured to assist in a campaign for an elected official. That’s why a member of the council can have election signs in their yard, but the same can’t be said about a city employee, Wager said [Sand, 2020.04.15].

Wager’s first sentence there makes some sense. The City Charter should insulate city workers from an overbearing mayor who might pressure them to help his campaign or face retribution from City Hall. But that point does not explain the Charter’s language prohibiting city employees from helping the campaigns of candidates running against current council members. To explain that prohibition, we have to appeal to a different intent: the Charter apparently doesn’t want people who work for the city campaigning for any candidate and creating the possibility of a quid pro quo—hey, I helped with your campaign, so now that you’re in office, how voting me a raise?

Councilman Dennis “Mike” Olson strongly criticized Mayor Schaunaman’s self-dealing effort to secure the city-funded rebranding contract. Mayor Schaunaman is helping challenger David Welling run for Councilman Olson’s seat. Should Welling win, Mayor Schaunaman could ask the city council for to let him bid for more city-funded contracts (which Councilman Olson said in February isn’t right) or to repeal the strict new conflict-of-interest policy (which Councilman Olson voted for) could turn to Olson’s replacement and say, “Hey, buddy, I helped you, now you help me.”

If the City Charter is concerned about city employees doing political work for an city council incumbent to preserve their paychecks, it should be just as concerned about a city employee, especially the top city employee, the mayor, doing political work for a city council challenger to advance his own political interests and personal profit.

Wager’s second sentence shows he’s not reading the City Charter consistently. Signs aren’t an issue yet (coronavirus means I don’t get out much, but on my few adventures to the south side of town, I haven’t seen any campaign signs yet), but the City Charter doesn’t explicitly prohibit city employees from displaying them. As a matter of fact, putting a sign in one’s yard may be one of the few political activities explicitly excepted from the Charter’s Conflicts of Interest provisions:

No city employee shall knowingly or willfully make, solicit or receive any contribution to the campaign funds of any political party or committee to be used in a city election or to campaign funds to be used in support for opposition to any candidate for election to city office or city ballot issue. Further, no city employee shall knowingly or willfully participate in any aspect of any political campaign on behalf of or opposition to any candidate for city office. This section shall not be construed to limit any person’s right to exercise rights as a citizen to express opinions or to cast a vote nor shall it be construed to prohibit any person from active participation in political campaigns at any other level of government [emphasis mine; Aberdeen City Charter Section 7.02(a)(5)].

Putting a sign in one’s yard expresses an opinion. The City Charter recognizes it cannot infringe on that core political speech. The Charter explicitly allows Mayor Schaunaman and everyone else who works for the City of Aberdeen to say what they want about candidates in city elections. They just can’t participate in city candidates’ campaigns with actions like circulating petitions.

But wait! Wager has one more really fun technical argument that could win me to his side:

Furthermore, before a nominating petition is filed, the person circulating the petition is not yet an official candidate, he said [Sand, 2020.04.15].

Now that argument I like: it hinges on law, definition, and best of all, the legal power of petitions. I have often said that a petition does not have legal force until it is submitted and that a candidate does not technically exist until the petition is filed and validated.Mayor Schaunaman circulated a petition to help Welling become an official candidate, but at the time Mayor Schaunaman circulated the petition, Welling wasn’t yet a candidate. Clever.

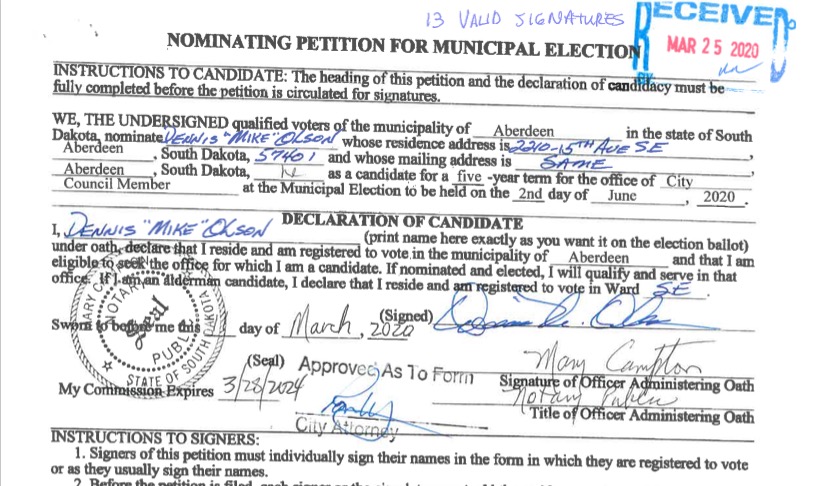

But guess who was a candidate when Mayor Schaunaman handled not-yet-technically-candidate Welling’s petition? Councilman Dennis “Mike” Olson:

Councilman Olson filed his petition on March 25. Mayor Schaunaman circulated Welling’s petition on March 29. At the time Schaunaman circulated the petition to replace Councilman Olson with Welling, Mayor Schaunaman was knowingly and willfully participating in an aspect of a political campaign in opposition to a candidate for city office.

City attorney Wager is making clear that he won’t support action against Mayor Schaunaman on this particular ethics issue, and it would seem likely the city council would not act contrary to its own attorney’s interpretations of the City Charter. But in this case, the City Attorney’s interpretation rests on shaky ground.

Nonetheless, the voters face a choice between an experienced and capable city councilman who has bravely opposed the mayor’s self-dealing, a businessman whom the Mayor has chosen to replace that ethics watchdog, or an Aberdeen businesswoman whose position on city conflicts of interest we eagerly await hearing.