The LRC hasn’t even posted the members or calendar of the interim county-funding study committee created last week by the Legislature’s Executive Board. But the Judiciary convened its HB 1064-mandated Indigent Defense Task Force last Friday and discussed one public service uniquely putting the squeeze on county budgets, the cost of guaranteeing the Sixth Amendment by providing public defenders:

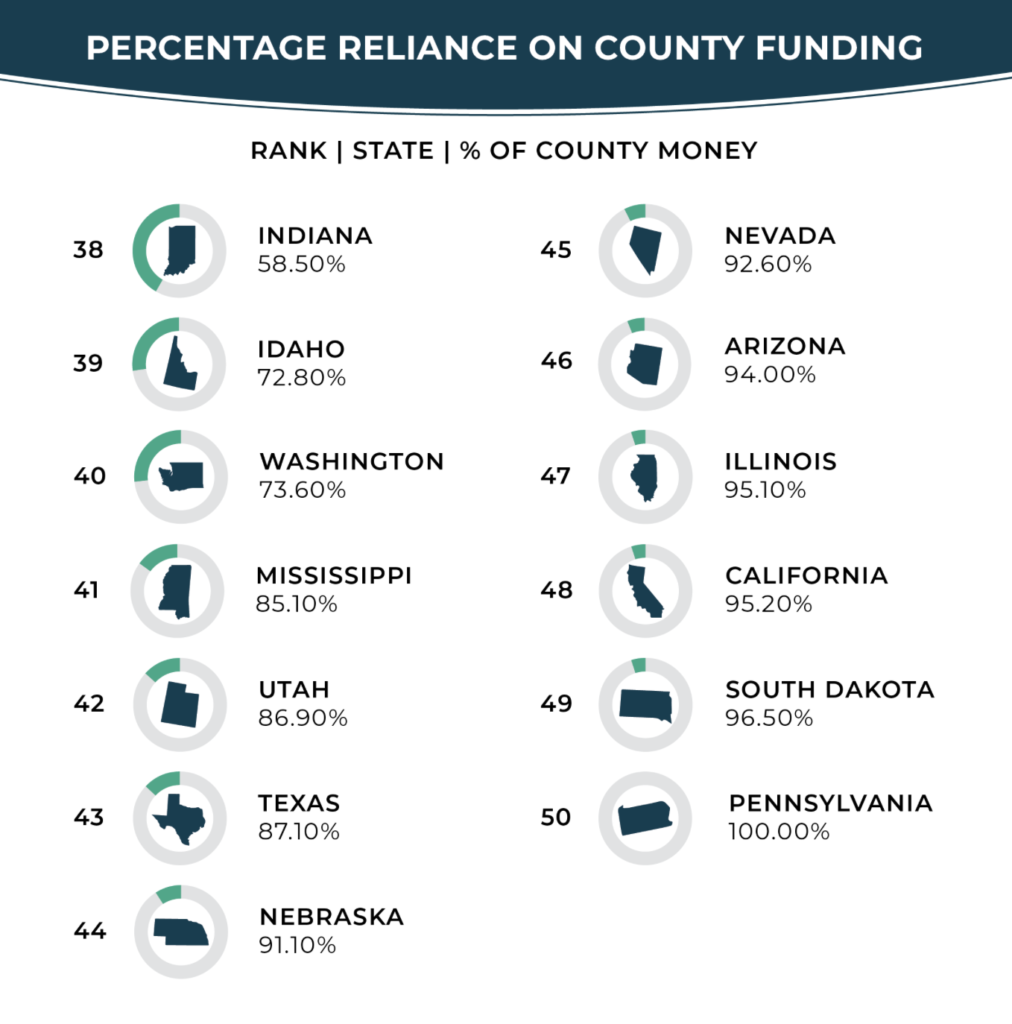

Only 11 states, including South Dakota, use local rather than state dollars to pay for the vast majority of public defense.

Just one state relies more heavily on counties to pay the cost than South Dakota, and that state – Pennsylvania – is now considering a five-year, $50 million investment in public defense.

South Dakota’s 66 counties, meanwhile, have seen their public defense costs for criminal cases more than double in the last decade [John Hult, “South Dakota One of Few States to Saddle Counties with Public Defense Costs,” South Dakota Searchlight, 2023.03.31].

The Sixth Amendment Center finds South Dakota counties bear 96.5% of the cost of providing indigent defendants with counsel:

The Sixth Amendment Center points out that states have both Constitutional and practical obligations to provide legal defense:

State government, not local government, is responsible for ensuring that every indigent defendant charged with a jailable offense is provided with a constitutionally effective lawyer. This obligation always rests with the state, even when a state delegates its right to counsel responsibilities to local governments. To fulfill its constitutional duty, the state must have a state-level entity that has the authority and ability to evaluate whether local indigent defense systems can, and in fact do, meet constitutional muster.

…National standards call for state funding rather than local or hybrid state-local funding because counties and municipalities most in need of indigent defense services are often the ones least able to afford them [Carroll and Goel, 2023.03.14].

But task force co-chair and USD Law dean Neil Fulton doesn’t want to hear that word obligation in this discussion:

Fulton, a former federal public defender, urged task force members to approach discussions on potential changes in South Dakota with an eye to effectiveness and efficiency.

“We should think about what we have an opportunity to do, not an obligation to do,” Fulton said at the start of the meeting. “We have an opportunity to really talk about how we make recommendations on what an effective system for representation is. Everybody here knows that when you have excellent, effective, ethical counsel on both sides of criminal defense, it’s better for everyone” [Hult, 2023.03.31].

It’s not an obligation, it’s an opportunity—like how your kids don’t have to do their chores, they get to? Sure, Neil, hand me that whitewash bucket….

Whatever word games Dean Fulton thinks he needs to play to get the state to do its duty, the task force needs to direct the Legislature’s attention to our neighbors, who find ways to cover those public defender costs:

Senior Attorney Aditi Goel of the Center offered a rundown of how differing states have approached and adjusted their models. Many of the states that previously relied on counties to fund legal aid have moved toward greater levels of state funding. Last year, Idaho pledged to move toward 100% state funding by 2024, for example.

Most of South Dakota’s neighbors already have similar setups. North Dakota and Montana fully fund indigent defense at the state level. Iowa funds defense for everything but municipal violations that are punishable by jail time. Minnesota funds all public defense at the state level, but allows counties to pitch in extra money [Hult, 2023.03.31].

A liberty-minded Legislature should be keenly interested in ensuring that every defendant gets Constitutional protection against the overwhelming law enforcement and prosecutorial power of the state. When the interim county-funding committee finally convenes, it should review the notes from the Indigent Defense Task Force and figure out how to take public defenders off the counties’ budgets.

I take Fulton’s comments to mean there is no need to think about or focus on the obligation, becauer4 it ids simply that – an obligation. There is NO getting out of it. There is no need to consider it further to that. Now, let’s focus on how we meet that obligation. But what do I know? It’s only my training and work experience as a professional facilitator that informs me on how get and keep a work group (task force) focused on the task at hand and not go wandering off on tangential distractions that informs my opinions.

I wonder how many clients Fulton was able to successfully defend. In the federal system it’s exceedingly rare to see an acquittal. And I’m actively watching.

State-funded does not mean better. Many state-funded public defender systems around the country have serious issues, including in Montana. https://rapidcityjournal.com/unconstitutional-public-defense-systems-upend-lives-freedom-across-west/article_42a696ac-57f8-5585-831a-701f0c41598e.html

While it is true that many public defender systems are tasked with too many cases, that problem is in part caused by the dedication of the lawyers that have been willing to work in relatively lower paying public defender offices. Such lawyers have a hard time exercising the ethical obligation to refuse to take new cases once they have an appropriate caseload. Sometimes the administrators of public defenders’ offices demand that attorneys take more cases than is approriate. If these lawyers would just say no, then the county or State would have to hire a private attorney to take such cases.

In my experience, attorneys that decide to work in public defender offices are in large part there because they have a desire to (1) help the most needy people in our population, (2) do what they can to assure that someone charged with a crime is treated fairly by the State, and (3) develop an expertise in the criminal law field.

Problems number (1) and (2) make it very difficult to say no, even when overworked. Problem number (3), according to my own anecdotal observations, frequently results in experienced public defenders that become much better at understanding criminal law and how to effectively defend someone charged with a crime than the most expensive private lawyers that usually represent rich people in civil cases, but do little criminal law. Based on a public defender’s experience and knowledge of the criminal law system, personally I would much rather have a public defender if I were charged with a serious crime than be represented by 95% of private attorneys.

The sheriff’s who arrest people are all constitutional scholars aren’t they? The arrested are undoubtedly guilty. Why bother with defending them?

Let it be noted that the local counties, of which 66 are twice as many as there should be, waste inordinate and immense sums of property tax collected funds on paying these wimpy public defenders, the bottom feeders of the lawyerly pursuits.

grudznick doesn’t know this for sure, but I wouldn’t be surprised if the young Mr. Krause didn’t get a substantial portion of his income from the county gravy train and the allegedly guilty indigent fellows who lurk about his area, being no-good-doers and rabble-rousers.

My careless mistake in using the term “problems” in describing the three motives of public defenders in the last paragraph of my comment at 2023-04-03 16:11. Indeed, the three motives I listed for engaging in this challenging field are laudable and highly honorable motives to act, not “problems” at all.