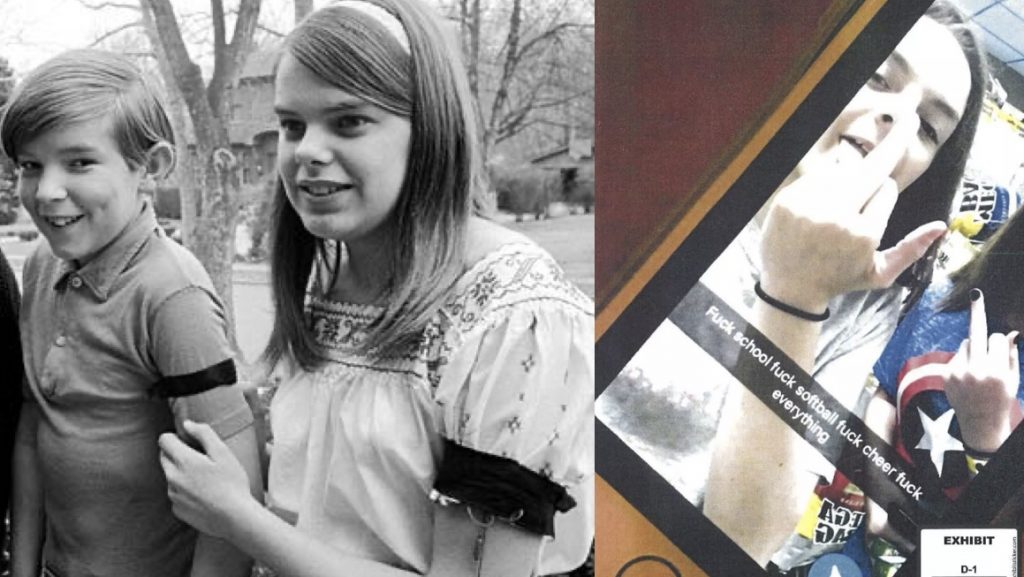

In its famous Tinker v. Des Moines decision in 1969, the United States Supreme Court affirmed the right of five students to wear black armbands to school to peacefully protest the Vietnam War. Yesterday the Supreme Court affirmed the right of a disappointed cheerleader to drop F-bombs on Snapchat.

NINA TOTENBERG: The case was brought by Brandi Levy, then a 14-year-old junior varsity cheerleader who failed to win a promotion to the varsity cheer team, as she explained in an April interview with NPR.

(SOUNDBITE OF ARCHIVED NPR BROADCAST)

BRANDI LEVY: I was really upset and frustrated at everything.

TOTENBERG: So she posted on Snapchat a photo of herself and her friend flipping the bird to the camera, along with a message to her 200-plus friends. It said – and here I’m cleaning it up for the radio – F the school, F cheer, F everything. She was suspended from the cheer team, but a federal appeals court ruled that the school had no right at all to discipline students for any off-campus speech. The school board in Mahanoy, Pa., appealed, and today, the Supreme Court ruled for Brandi, while at the same time declaring that schools may in fact punish some speech, especially speech that is harassing, bullying, cheating or otherwise disruptive [Nina Totenberg, “Former High School Cheerleader’s F-Bombs Are Deemed Protected Speech,” NPR: All Things Considered, 2021.06.23].

The speech in question in Mahanoy v. Levy falls short of the social activism and advocacy of the Tinker plaintiffs. The speech affirmed in yesterday’s ruling was vulgar, impulsive, ill-considered, selfish, and of little social or historical value.

“The vulgarity in B.L.’s posts encompassed a message, an expression of B.L.’s irritation with, and criticism of, the school and cheerleading communities,” Breyer wrote.

“It might be tempting to dismiss B.L.’s words as unworthy of the robust First Amendment protections,” Breyer said. “But sometimes it is necessary to protect the superfluous in order to preserve the necessary” [Debra Cassens Weiss, “Cheerleader’s Snapchat Vulgarity Had a Message, Supreme Court Says in 8–1 Ruling Against School,” ABA Journal, 2021.06.23].

Tinker was a landmark ruling, but it cut both ways: while establishing that students and teachers do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate,” it established the “substantial disruption” standard allowing schools to restrict First Amendment activities when then they can demonstrate that “engaging in the forbidden conduct would materially and substantially interfere with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school.”

Similarly, Mahanoy v. Levy is not a pure victory for First Amendment activists. This ruling does not say that students can say whatever they want outside the schoolhouse gates without facing punishment from the school. Mahanoy leaves the door open for schools to regulate student conduct outside of school; it simply reminds them that they have to “satisfy Tinker’s demanding standards” and go an extra mile to apply those standards for student activity off school grounds and outside school time.

While the Court wimps out and declines to establish clear boundaries between on-campus and off-campus speech and the schools’ regulatory power thereover, Mahanoy identifies three key characteristics of off-campus speech that complicate schools’ regulatory efforts and make their suspension of young Levy for her Snapchat outburst unsupportable:

Particularly given the advent of computer-based learning, we hesitate to determine precisely which of many school-related off-campus activities belong on such a list. Neither do we now know how such a list might vary, depending upon a student’s age, the nature of the school’s off-campus activity, or the impact upon the school itself. Thus, we do not now set forth a broad, highly general First Amendment rule stating just what counts as “off campus” speech and whether or how ordinary First Amendment standards must give way off campus to a school’s special need to prevent, e.g., substantial disruption of learning-related activities or the protection of those who make up a school community.

We can, however, mention three features of off-campus speech that often, even if not always, distinguish schools’ efforts to regulate that speech from their efforts to regulate on-campus speech. Those features diminish the strength of the unique educational characteristics that might call for special First Amendment leeway.

First, a school, in relation to off-campus speech, will rarely stand in loco parentis. The doctrine of in loco parentis treats school administrators as standing in the place of students’ parents under circumstances where the children’s actual parents cannot protect, guide, and discipline them. Geographically speaking, off-campus speech will normally fall within the zone of parental, rather than school-related, responsibility.

Second, from the student speaker’s perspective, regulations of off-campus speech, when coupled with regulations of on-campus speech, include all the speech a student utters during the full 24-hour day. That means courts must be more skeptical of a school’s efforts to regulate off-campus speech, for doing so may mean the student cannot engage in that kind of speech at all. When it comes to political or religious speech that occurs outside school or a school pro- gram or activity, the school will have a heavy burden to justify intervention.

Third, the school itself has an interest in protecting a student’s unpopular expression, especially when the expression takes place off campus. America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy. Our representative democracy only works if we protect the “marketplace of ideas.” This free exchange facilitates an informed public opinion, which, when transmitted to lawmakers, helps produce laws that reflect the People’s will. That protection must include the protection of unpopular ideas, for popular ideas have less need for protection. Thus, schools have a strong interest in ensuring that future generations understand the workings in practice of the well-known aphorism, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” (Although this quote is often attributed to Voltaire, it was likely coined by an English writer, Evelyn Beatrice Hall.)

Given the many different kinds of off-campus speech, the different potential school-related and circumstance-specific justifications, and the differing extent to which those justifications may call for First Amendment leeway, we can, as a general matter, say little more than this: Taken together, these three features of much off-campus speech mean that the leeway the First Amendment grants to schools in light of their special characteristics is diminished. We leave for future cases to decide where, when, and how these features mean the speaker’s off-campus location will make the critical difference. This case can, however, provide one example [Justice Stephen Breyer, Opinion of the Court, Mahanoy v. Levy, 2021.06.23, pp. 6–8].

Our kids (and a lot of adults) still need to learn to use the Internet appropriately, to recognize that their online speech (especially when broadcast to hundreds of people who can amplify that message with screenshots and retweets) is largely public, that such online expression can have consequences for which they can be held accountable. Our kids also need to learn to think before they f-tweet.

But in this case, it was the parents’ job, not the school’s, to tell their daughter not to do the electronic equivalent of walking down Main Street flipping the bird at everybody and to ground her from her phone for a couple days.

I love it when the Supremes get it right.

You’re saved, grudznick.

“it is necessary to protect the superfluous in order to preserve the necessary…”

If you have ever been an adolescent, you have probably uttered phrases very similar to Brandi Levi regarding something about school. I’d rather hear such venting, than that students internalize all their frustration and turn it destructively on themselves or others at school. Venting is a healthy thing. If she had done it over the old rotary phone, as kids in my generation did, it would be a moment you wouldn’t want your parents to hear, but it wouldn’t screw with your next year of activity participation. But now kids vent on social media, which lasts forever. Technology isn’t always your friend.

I would occasionally overhear such venting from my daughter about something that happened in debate. Kids talk the way kids talk. In my generation the F-word was a big deal.When you said it, you meant it. In her generation it had become the all-purpose word. I wasn’t too happy about her potty mouth, but I also didn’t make a big deal about it. We discussed it once, and she said it was just the way kids talk, and it doesn’t mean anything. “Well then why say it?” She had no answer, though I think she muttered something about me saying it. Generally, she would have presented an argument that made sense, but her what-aboutism made her think she won the debate we were having about the F-word.

Her younger cousin once rolled off a sting of cuss words, and, realizing we had overheard him, explained, “Excuse me. That’s just the way we talk in Sioux Falls.” Indeed. And probably everywhere else in the country.

I cannot recall ever hearing, my parents who were not religious, ever swear, in their 90+ years. I, on the other hand, stopped using the F bomb,( f–kin aye) when I left the service. Swearing is just a weak mind trying to be forceful.

Well..cibvet,,,of course you are correct. As my father used to say “He knew not what to say, so he swore.” The speech in question was obnoxious and quarrelsome but it was not uttered (Or recorded, whatever Facebook does) within a public purview governed by the School Board, thus the Board exceeded its authority in sanctioning the speech. The speech was merely commentary, it did not threaten anyone’s health or welfare.A case of the limits of free speech being defined. I’m also pleased Clarence Thomas concurred

Who gives a f…?

Weak mind, I think not. Like Shakespeare’s mind? Lot’s of swearing and dirty words from the works of the best writer of all time. He even made up his own swear words and double entendres. There’s an art to swearing. The thing about swearing is it loses its punch if used too often. Teens use the F-word so much, when talking to their own cohort, that it is just doesn’t mean the same thing as when you hear it from someone only once.

Weak mind, I think not. Patton was the furthest thing from a weak mind. A swearing affliction to comfortable ears and social nonsense (norms) motivates, informs, delivers urgency, and substitutes for when other senses are absent (think war, think the series, Deadwood). There is a fine art to swearing.

There’s reliable science behind the fact that people who swear often tend to be more honest and genuine than those who don’t. Not to insult anybody’s parents, of course… just sayin.

Well..I suppose I should say F..k.n A

Well..I suppose I should say F..k.n A by the way Clarence Thomas did not concur with Breyer’s majority opinion (7-2)..Ailito did though for reasons other than cited by Breyer…

Seems that using Shakespeare, Patton and reliable science to condone swearing is probably enough to make anyone begin swearing. I wonder how many of you Christians would use foul language in front of Jesus. As an agnostic I’m unaware but, maybe he accepts,”they did it so I can too”. Ask your pastor with an expletive laced question and post your answer.

What quotable expletive deleted quote do you reckon G. A. Custer uttered when he saw all those Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne warriors ascending last stand hill to make his acquaintance on this date in 1876?

Well..all we know is that when Custer left the coulee and went to the top of the bluff he gave his bugler a message for the officer commanding the trailing mule train…..”Hurry Up, Big Village, Bring Packs…PS Bring Packs”…extra ammunition was in the packs. By that time his Crow Scouts had sung their death songs and were looking for a way to escape.

Custer did not smoke or drink and never swore….people find that unusual now and they did then.

Not as eloquent as Arlo, but…

We also all generally know since Black Elk Peak was named, that September 3, 1855, General Harney sat on his horse at midnight on the confluence of the North Platte River and Blue Water Creek (now Lewellen NE) and exhorted his cavalry, his infantry and his artillery, in effect as follows: “Those savage bastards, they killed Lt. Grattan and his boys, and they are sleeping right up this here creek. Now lets give it to them sons-of-bitches hard, no quarter!” The mounted soldiers silently slipped up ahead of the rest of the 600 troop, surrounded the Little Thunder village of some 100 Sichangu (Brule’) tipis and another 40 some Oglala tipis. Attack was at first light after a parley where Harney said to the Chief, “I’ll give you an hour to run.”

80 some Lakota men, women and children were ridden down and massacred in cannon fire, infantry assault and a running chase over several miles from the burning tipis. Some 70 captives were marched to Ft. Laramie and imprisoned. Harney’s surveyor had the bloodied Indian “battlefield artifacts” boxed up and waggoned back to his and the General’s eastern homes. See “The Little General’s Collection”, The Smithsonian.

Avenging the starving Morman cow of 1854 by the US Government was now complete. Thus Custer’s madness began.https://history.nebraska.gov/collections/gouverneur-kemble-warren-rg3944am

Leslie–two books about the clash of cultures that resulted in so much tragedy for both cultures are Tom Power’s “Killing Crazy Horse” (not the Bill O’Rielly Killing Crazy Horse” ) and Nathanial Philbrick’s excellent revisionist history “the Last Stand” If you want the soldier’s perspective Charles Windolph was a 20 year old member of the Custer Expedition and was the oldest surviving soldier at the Little Big Horn. aAt 90 he sat down for a month with two historians and narrates “I Fought With Custer”. He was a member of Benteen’s troop.He spent most of his life as an engineer for Homestake Mining Company and died in Lead in his 90;s. His is a very human tale.

Thank you Arlo.

And interesting tidbit after kids asked some questions about Greasy Grass and the treaty.

“…Congress voted in 1991 to rename Custer Battlefield National Monument the Little Big Horn Battlefield National Monument. In the year before the change, the National Park Service received a steady flow of mail filled with racist slurs and other hate speech against the name-change, these missives bolstered by a twisted patriotism and labeling of the move as everything from a travesty to treason.”