South Dakota continues to rock out on getting coronavirus vaccine into South Dakotan arms. According to the vaccine page of the Department of Health’s covid-19 dashboard, we’ve given 14,799 South Dakotans their first shot of the two-dose vaccine. That’s up from 7,844 last week; at this rate, we could get first doses into our entire population of 23,171 Phase 1a frontline medical workers and first responders by next week and have them all second-dosed (gotta wait three or four weeks!) before the end of January.

So when’s our turn to roll up our sleeves and get our coronavirus shots?

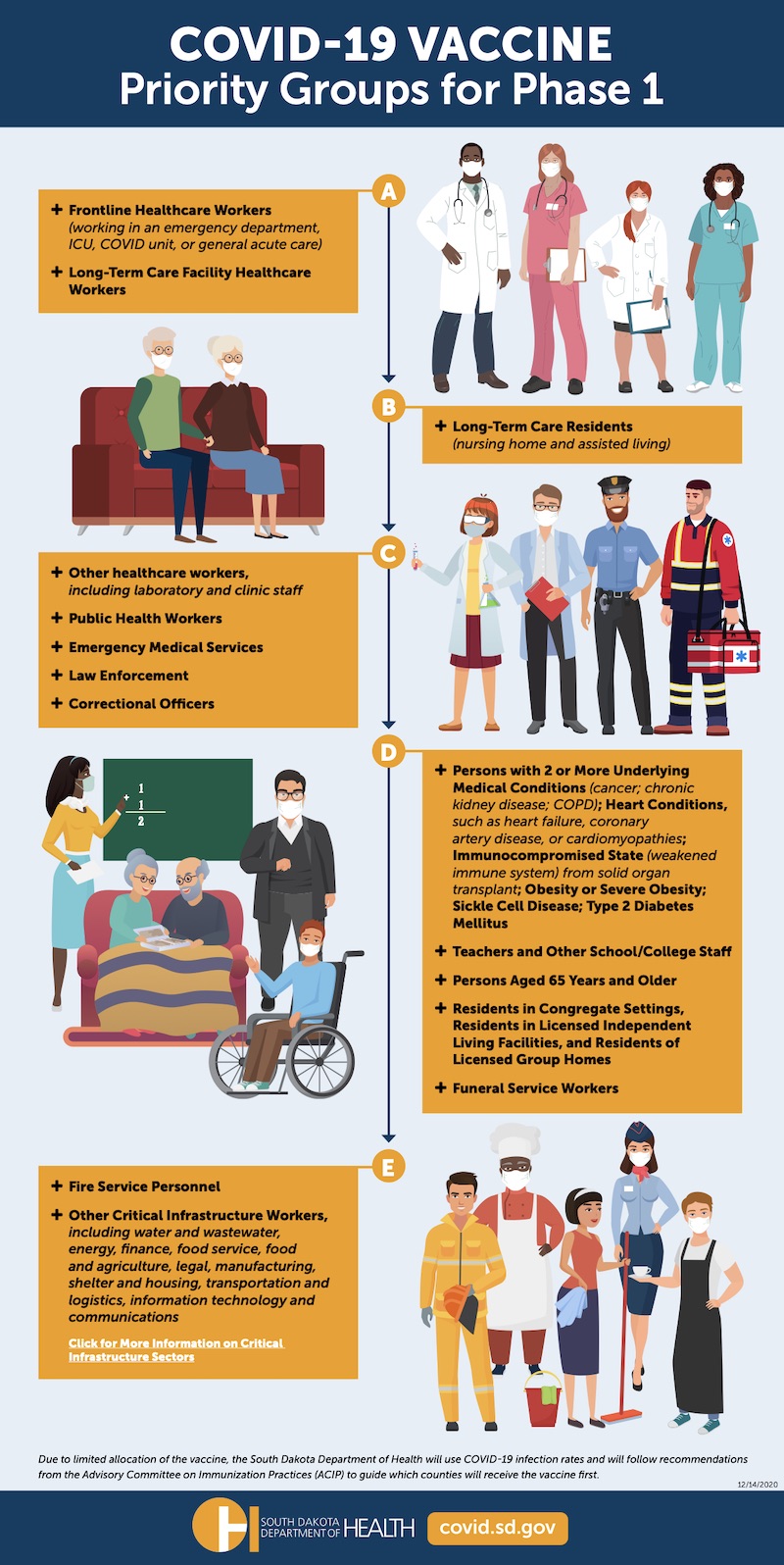

As I review South Dakota’s coronavirus vaccination plan, I find that, as a college staffer, I get to line up in Phase 1d, behind long-term care residents (Phase 1b) and health care workers not covered in the first round, public health workers, emergency medical services, law enforcement (Jason Ravnsborg?), and prison workers (Phase 1c). I’ll get to line up with my college’s faculty (and all other teachers) and my mom and dad (folks 65 and over). Also included in Phase 1d are folks with serious medical conditions, funeral service workers, and “residents in congregate settings,” who I assume include the prisoners who will get their shots after their guards.

There’s just one more priority group, Phase 1e, which includes firefighters and “critical infrastructure workers.”

I notice that “critical infrastructure workers” does not appear to include the industry sector in which the other half of my working household earns our bread: clergy. Some of the protests against reasonable public health precautions have focused on arguing that churches are too important for the government to limit in-person worship, despite the proven heightened risk of coronavirus transmission in church gatherings. Yet South Dakota appears to be telling pastors and priests that their work does not warrant early access to the coronavirus vaccine.

I can hear the argument that our spiritual infrastructure is surely as critical as our physical, educational, and economic infrastructure. But I can also look at the many ways my wife and her fellow clergy can conduct their spiritual work remotely. The same applies to my work on my campus: as registrar, I do most of my work in front of a computer. Move all of my meetings to Zoom, handle all requests by e-mail or video chat, and I don’t need to pose a disease transmission risk to anyone in my institution.

My wife and I can both identify elements of our work (far more in hers than mine) where face-to-face contact is helpful and preferable. But with the cooperation of our institutions and sensible choices by the people we serve, we both can find ways to provide our services without crowding into line for valuable but limited vaccines.

Besides, why should we worry? If South Dakota keeps cranking through its vaccine plan at current rates, and if Pfizer and Moderna and UPS and FedEx and President Joe Biden can keep the supply chain moving, South Dakota may be able to shoot up everyone in Phase 1 and starting vaccinating the general public fast enough to make our worries about the Phase 1 line-up academic.

But until then, we’ll keep staying home when we can and masking up when we can’t.

That’s so typical…

For many this is mere mythology: “spiritual infrastructure”, not “as critical as our physical, educational, and economic infrastructure.” And equality in all the latter.