Last updated on 2021-08-04

I’d been thinking about Stephen King’s plague novel The Stand since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. In that novel, a flu virus engineered (unlike the real coronavirus, which is worse than the flu but for which there is no clear evidence of laboratory origins or human engineering) by the U.S. military gets out and kills almost all of humanity in a couple weeks. (And that’s just King’s way of setting the stage for the novel’s real cosmic conflict.) Having read The Stand in my formative years and thus always carried that dreadful apocalyptic vision in my worst-case-scenario soul, I found some relief as March and April and the rest of our dreadful 2020 dragged along and left most of us alive to worry and complain and wait for vaccines.

But I didn’t feel like picking up The Stand for a reread (or any other plague novel or movie, for that matter) until this spring, two weeks after I got my second Pfizer shot, when the pandemic seemed controllable, beatable, and headed for past tense. I spent much of our plague year reading the far less frightening Robot and Foundation novels, the works of Isaac Asimov that figured prominently in my youthful reading. I read them now in French translation—rereading familiar stories in a foreign language makes it easier to guess new words in context and quickly build vocab—and I read them all on my iPad, an antidote to my lingering teenage end-of-the-world pessimism, because I could lie in the dark toward midnight, reading and swiping those glowing pages and shout back at my 1980s self, Dude! Check it out! You will live to have a magic book, thinner than the tablets Captain Kirk had, able to pull novels and news from all over the world! And when you wake up, you can switch on the same device and write and publish your own stories! The future is awesome!

I read the original 1978 Stand before King published his extended cut in 1992. King’s extended version is 58% longer than the original; it spans three 500-page-plus volumes in the French translation I found. I finished the first volume, to the conclusion of the super-grippe, on July 4 (the same day in the novel that protagonist Larry Underwood wakes up, sings The Star-Spangled Banner naked to the dawn’s early light, then finds his first post-plague companion dead in their tent of an overdose and despair). I was halfway through the second volume, in which the survivors cross a cadaver-strewn America to choose their sides in the real storm to come, when Stu Whitney sent me his plague book:

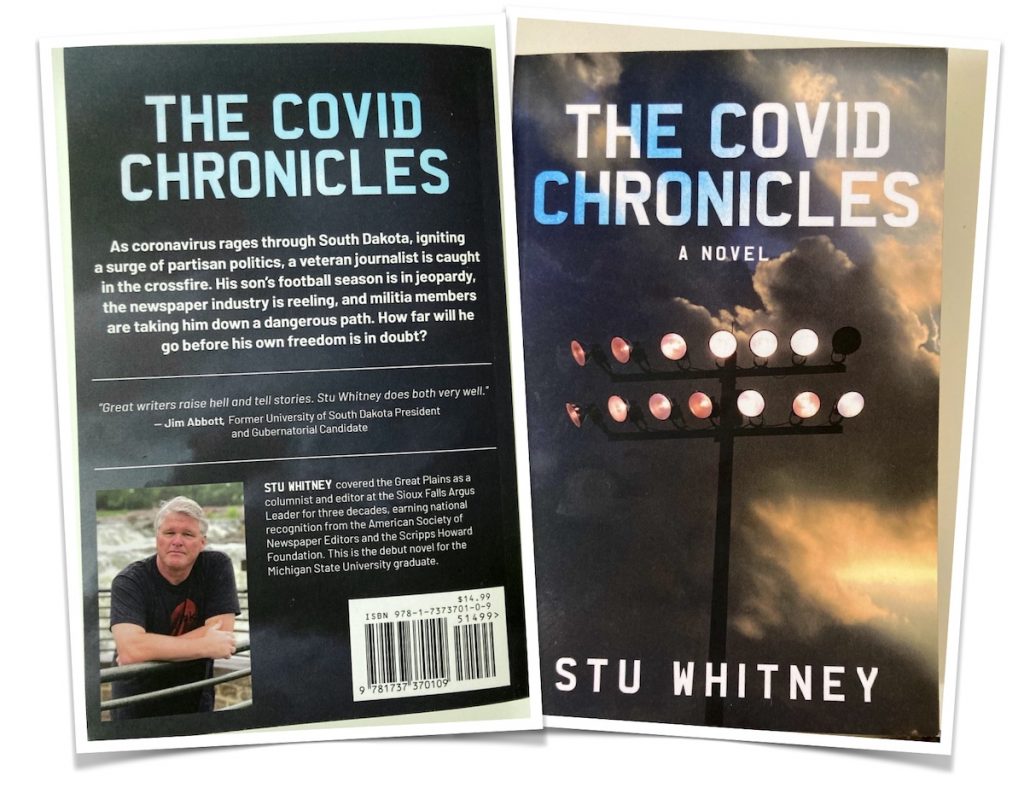

The Covid Chronicles is the longtime Sioux Falls journalist’s first novel, set in Sioux Falls amidst the coronavirus pandemic. At a slim 220 pages, Whitney’s work appears by my rough word count to weigh in at maybe a tenth of King’s epic. The Covid Chronicles promised a quick read, but did I want to interrupt my long, luxurious swim in a grand fantasy about a plague that wasn’t, further insulated by the constant pleasant diversion of looking up new French words and idioms (Hey, 1980s-me! Your magic glowing book will include access to a global dictionary!) to take on a new novel, on plain old paper, a grim tale set right here in South Dakota, speaking of the plague that was, the plague that is, the plague that has taken lives, separated friends and families, and (I’m not sure I want to share this part with 1980s-me) shaken my faith in the ability of my neighbors to confront and conquer great danger?

Truth can be scarier than fiction… but I set my iPad aside and took up Whitney’s novel.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, and institutions are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictionally in conjunction with actual events [opening disclaimer, Stu Whitney, The Covid Chronicles, 2021].

The truth that makes The Covid Chronicles scary comes not in a journalistic account of factual details of a mishandled public health emergency, of attempts by politicians and right-wing extremists to manipulate the press, or of citizens led astray by false information and f’ed up priorities. Sure, the narrator looks a lot like the author—Michigan-raised, sports writer turned newsman and columnist, working at a Sioux Falls paper battered by the Internet and corporate downsizing. The novel’s Mayor, Governor, Governor’s aide, and hospital CEO clearly track public figures and public statements we heard on the news (although Whitney models his fictional Sioux Falls mayor on Mike Huether, not Paul TenHaken, to heighten the partisan tension crucial to his plot). The historical details of the novel—a city built on usury, a powerful hospital tied to a usury magnate, a meatpacking plant racked by covid—mirror the story of our Sioux Falls.

But do not misread this novel as history, journalism, or autobiography. Whitney says at the top that The Covid Chronicles is fiction. I take the author at his disclaimer word and read his book as fiction. Fact-checking page by page (how much of that quote did Whitney borrow verbatim from Maggie Seidel? Did the mayor and the editor really have that conversation? Was there a connection between the domestic terrorists who threatened to kidnap and kill Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer and the folks who showed up to oppose mask mandates in Sioux Falls?) misses the point of a novel. When we read fiction, the proper questions are (1) Does it hang together as a good story? Is it worth reading? and (2) What is it trying to tell us? What can we learn and apply to our real lives?

To the first question, yes, The Covid Chronicles is worth reading. Whitney crafts a coherent story that works as the pandemic tale the title promises, a political thriller, and most importantly, a personal tragedy.

As in The Stand, the pandemic arguably plays a secondary role in The Covid Chronicles, setting the stage for the primary conflict without being the focus of the conflict. Whitney’s protagonist struggles to balance his concern about catching and spreading the virus with his desire to see his son play high school football. He lets his own caution lapse and subsequently finds his whole family apparently infected. But unlike The Stand, the main characters do not see their loved ones suffer gruesome deaths from the pandemic. We hear about the suffering and death of others, covered with the journalistic reserve of the narrator and his newspaper, but those specific losses inform the plot without changing the course the main characters follow through the plot in their primary conflicts

Besides, Whitney’s protagonist is a journalist, not a virologist, and in his very first paragraph, a full spoiler to his own story, he makes clear that the man-versus-nature conflict becomes irrelevant to him:

My dedication to mask-wearing, the subject of dozens of self-important columns and fatherly lectures during the rise of the Covid pandemic in the Upper Midwest, has become as negligent as the guards will allow. The virus has raged through prison populations, and they tell us vaccines will be here soon, but I don’t think much about it. The odds of finding contentment when I’m released are as unthinkable as the crime I committed, which resulted in the loss of a life, the ruination of my family and career and the realization that my words, once respected are viewed as desolate overtures from the opposite side of the wall [Whitney, pp. 1–2].

The story revolves far more around the conflicts of man versus society and man versus self.

As a political thriller, The Covid Chronicles shows a journalist documenting and becoming swept up in the political forces shaping the public policy response to the pandemic. The novel’s Republican governor of South Dakota is focused on raising her national profile and uses a laissez-faire approach to the pandemic to burnish her Trumpist credentials. The novel’s Democratic mayor of Sioux Falls wants firmer leadership and active countermeasures to protect his city and his state (“…let it be known that personal responsibility is not enough,” the mayor says in a November press conference. “Telling people to wash their hands is not enough” [p. 153]). The mayor has clear aspirations to run for Governor someday, and the Governor knows it. This political conflict makes more tense their practical conflict. Both attempt to use the press, and the protagonist’s newspaper specifically, to their advantage. The mayor fosters a working relationship with the journalist, providing confidential tips, while the governor, through her policy director, newly hired from “far-right think tanks in Washington, D.C.” [p. 23], attacks the journalist’s work and integrity and ultimately threatens the journalist personally. Even as the governor’s aide openly mocks the Sioux Falls newspaper, she evidently still views it as a vital political influencer, as she and other allies of the governor conspire to win the protagonist to their side and control the narrative of pandemic politics.

That conspiracy and the virus itself appear to work together to contribute to the main thread of the novel, the personal tragedy. The conspirators lure the protagonist into a situation that compromises his health, his family, and his professional integrity. Yet as the trap unfolds, the protagonist misses clear signals that I have trouble believing an experienced journalist would miss. As he drove further into his damnation, I found myself shouting at the protagonist, How dumb are you?!

The narrator’s blindly bad decisions, culminating in the final bad decision that leads to the “unthinkable” crime he mentions on page 2, come amidst the “cerebral fog, an unwelcome companion since my bout with Covid.” Brain fog is a well-attested and persistent of covid-19. A sympathetic reader could conclude that the unthinkable crime was really an unthinking crime, brought on by cognitive dysfunction.

But it ain’t tragedy if hero can rightly cry, “The devil made me do it!” In tragedy, the hero opens the door for the devil, in this case a tiny, many-horned devil that only weakens a brain already beset by the hero’s own fatal flaws. The narrator falls in with bad dudes (a weakness prefigured when the narrator tells of hanging out with some bad kids back in Michigan during a tough time in his childhood—there’s that narrative coherence, tales told for a reason, the sign that Whitney thought through what he was writing). Snarled in the experience of his dad’s departure and detachment, the narrator places his son’s opportunity to play football above evidence, values, and his own public calls for “sacrifice” that could have averted his personal downfall. The narrator’s focus on sports is so overriding that, knowing the fatal impact of his ultimate bad decision, he takes no action other than to stay and watch the end of his son’s football game.

The protagonist admits he is his own devil. His selfishness leads to his downfall. His selfishness leads the loss of everything he values (“I could have put my foot down and told Nathan that there are were more important things than football, that we needed to make sacrifices to protect others from the spread of illness, but that didn’t happen” [pp. 138–139]). His selfishness leads to “sudden, undignified death” (a phrase applied on p. 29 to an early covid victim but applicable to the victim of his own crime toward the end). Those dumb decisions didn’t come from any viral brain fog; they came from his character.

And therein lies what The Covid Chronicles may tell us about the coronavirus pandemic in South Dakota.

People died (and more are dying) because of who we are, because of choices we made, because of decisions arising from our own culture. We can rally to rescue people in sudden danger that we can tackle with swift manly physical courage (witness the rescue of a woman and her dog from a collapsed building in downtown Sioux Falls, in which a rescue worker extends a gloved hand through the rubble, takes the woman’s hand, and says, “We have you, and we’re not going to let you go” [p. 15]), but we cannot respond with the same brave community spirit to a long-term public health crisis that requires us to change our daily habits and sacrifice Friday night sports and Saturday night wings and beer.

We are the protagonist in The Covid Chronicles, hobbled by our selfishness. Confronted with a deadly pandemic, we failed to see beyond ourselves to statistics, science, and social responsibility. We saw people dying, and we kept going to ball games (and rodeos, and CPAC…).

At one game, the narrator recalls a team that had to “punt into gale-force winds, watching in horror as the ball sailed backward over their heads and through their own end zone for a game-deciding safety” [p. 147]. The backward punt symbolizes the futile efforts of writers to speak truth to South Dakota’s powers, only to see their critiques blown back as evidence of a liberal media plotting in bad faith against good and true South Dakotans and thus scoring more points for the one-party regime.

But that image captures a broader futility of words that the disgraced (think about that word) protagonist feels in the prison cell where he begins and ends The Covid Chronicles. He says letters from prison “speak of pain and isolation and missed warnings, of moments where lives could have been lifted but instead teetered and splintered, their pieces a mere hint of the whole” [p. 8]. He senses that he has spent his career and especially the coronavirus year writing letters from the prisons of his culture and his personal sins, warnings missed by everyone, including himself, as South Dakota slid into ruin.

Yet he clings to some shred of hope. He recalls the words of an Indian inmate: “Find a way out of prison every day” [p. 8]. Moments later (in the novel timeline; 212 pages later in our hands), the narrator harkens (ah, more narrative coherence, images staged early for later deployment—good work, Stu!) to an earlier recollection of waiting down the block for his father to come home and wonders if his writing could still lead to forgiveness:

The scratching of pencil on paper soothes me as I look ahead to days and weeks and months to come. I wonder when this all ends and we take stock of ourselves, like refugees from a vast war, how my words will be received by those I have failed. Does understanding lead to forgiveness, or do fragments of betrayal linger, keeping normal beyond our grasp? I pour out my words and await their response, a child on the street corner, watching the cars, searching in vain for the right one, then beginning the long walk home [Whitney, p. 220].

Such forgiveness may be hard to find on a prairie that our Michigander narrator calls “graceless” [p. 9]. Again, think about that word. Graceless echoes grassless, an odd word to hear in what should be a sea of grass. Grace, too, refers to something we’d think we’d find in abundance in a place thick with Christian churches. When the narrator mentions grace, he isn’t speaking of elegance or poise. By grace, he means Lutheran grace, forgiveness and salvation extended to the unworthy. The narrator’s final image is of a grace that does not come and leaves us walking home alone. Such grace, The Covid Chronicle warns, may elude us all—writers, mayors, governors, friends and neighbors—whose crime of selfishness resulted in the loss of life amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The Stand rescues its remaining heroes by pure grace (a conclusion 1980s-me found somewhat dissatisfying, as I expected my Jim Kirks and Lije Baleys to forge their own salvation). The Covid Chronicles ends with no such promise to its protagonist, who stands for me and all my fellow South Dakotans. Stu Whitney may thus have offered a scarier conclusion to his pandemic novel than Stephen King. Whitney has shown us our inability to stand together. Whitney leaves us to bear our guilt for our real pandemic and wonder who, if anyone, will grant us grace.

Undoubtedly, the best book report of the pandemic.

Félicitations

That’s one long blogging, Mr. H, so I didn’t read it real carefully for fear of spoilers.

But I gotta know, does Mr. Whitney cast the blogger, Mr. E, as Trashcan Man? That’s grudznick’s favorite character. No, don’t tell me, don’t, I want to find out as I read it!

Not able to render judgement without reading your source. Will say, however, quoting Jacques Lacan, that ” truth is structured like a fiction.” This suggests that the best of fiction is in many ways the closest we’ll ever get to the ineluctable we like to think must certainly be the truth.

I maintain that the best of science when it by definition reflects empirical reality back to us, does us the greatest favor possible. If that reflection is the best we have, so be it. Is there some better? If so, what is it, other than our own elucubrations divorced from the empirical?

Bloggers make no appearance in this novel, Grudz. The narrator attributes some of the decline of the newspaper to the availability of free content online, but he refers to newspaper content, not independent/amateur online publications.

Thank you, Porter. Whitney’s novel provides a lot of good material. The prison metaphor could provide the framework for a whole separate essay on South Dakota culture.

Ah, this reminds me once again of that early morning in Clay County when, as I was returning from a decade and a half of life in the uber civilized social clime of the West coast, my reaction to passing through what I had wanted to remember with fondness, my SD roots. My gut reaction to seeing the reality of “my” SD – now from an “outsider” perspective, was a mixture of sorrow and nausea. I wondered what I was thinking to have come to the decision to make my return. I still wonder.

Richard, Whitney’s novel includes some other interesting symbolism and commentary on that culture and the perception of “outsiders” that could make for a whole nother essay. I’d enjoy teaching this book in the classroom, as it offers a number of good discussion/essay topics. It would make an interesting entry in any class on South Dakota literature, given its quality and its unique topicality.

You can read that Sioux Falls paper’s review of its former writer’s novel here.

You can find the author himself selling and signing copies of his self-published novel at Zandbroz in downtown Sioux Falls on Saturday, August 14, 2–4 p.m.

“We are the protagonist in The Covid Chronicles, hobbled by our selfishness. Confronted with a deadly pandemic, we failed to see beyond ourselves to statistics, science, and social responsibility. We saw people dying, and we kept going to ball games (and rodeos, and CPAC…).”

This^ is how societies collapse. It’s not some dramatic apocalypse. It’s the slow degrading of the social contract. I believe I have posted this link before here, but it’s about how Sri Lankan society collapsed and how America seems to be in the process of collapsing.

https://gen.medium.com/i-lived-through-collapse-america-is-already-there-ba1e4b54c5fc

I’ll have to read The Covid Chronicles. Meanwhile, Albert Camus’ The Plague is an excellent (if highly depressing) read – and Cory, you can read it in French, as I have. And again, we are all the protagonist in that novel, too.

Great suggestion, Eve!

From Donald’s Sri Lankan article: “If you’re trying to carry on while people around you die, your society is not collapsing. It’s already fallen down.”

The author wrote in September 2020 as coronavirus deaths rose and the White House remained in the hands of a tyrant. How much better off are we now? Have we at all forestalled or remedied the collapse that Sri Lankan author saw?

Whitney’s former newsroom colleague John Hult reacts to Whitney’s decision to hunker down and write his first novel in this Pigeon605 essay.