The Class Act of the Week is Democratic Senator Jim Peterson (D-4/Revillo). Senator Peterson proposed Senate Bill 136 this year to incentivize grassy buffer strips along South Dakota’s lakes and streams to reduce erosion and runoff and improve water quality. Senator Peterson’s bill passed both the Senate and the House, only to be vetoed by Governor Dennis Daugaard. Now that Governor Dennis Daugaard rolls in with his own riparian buffer strips legislation, how does Senator Peterson respond?

He praised Daugaard on Monday for taking up the cause.

“I think the governor’s version is a better version than the one I wrote,” Peterson told the taskforce.

…Peterson spoke with appreciation for the administration’s willingness to preview the bill for the taskforce, whose members include legislators, county assessors, and agricultural producers.

“I think it was really great you brought this to this committee,” Peterson told [Revenue Dept. tax wonk Michael] Houdyshell, adding there is now time to vet the legislation. The 2017 session opens in three months [Bob Mercer, “Governor Intends to Offer Buffer-Strip Tax Break,” Black Hills Pioneer, 2016.10.18].

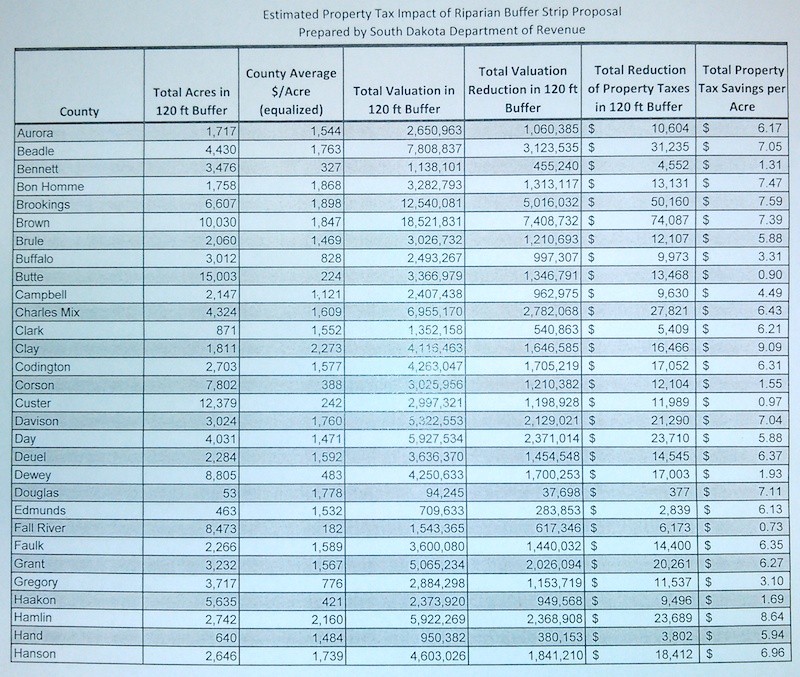

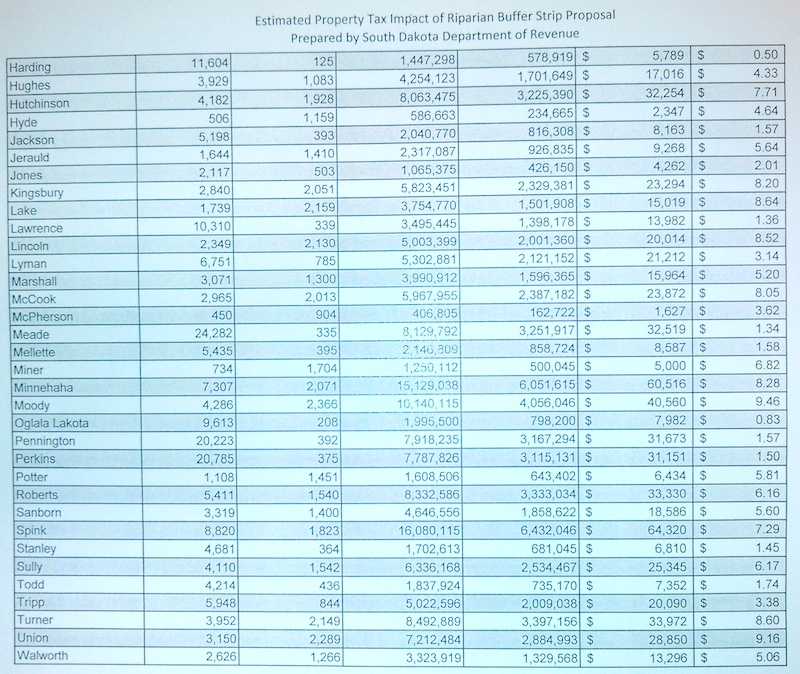

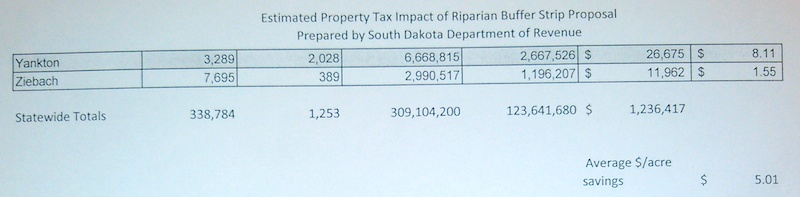

The Department of Revenue presented the Ag Land Assessment Task Force with the following spreadsheet showing the estimated cost of the Governor’s plan (I got these photos at the Coteau Area Conservation Districts Legislative Banquet in Webster Monday evening):

Eight counties have more than 10,000 acres that would qualify for the riparian buffer strip incentives in Governor Daugaard’s plan, but only one of those counties, my own Brown, is in East River. West River counties, generally drier and used for grazing rather than crop production, have lower land values; Brown County’s qualifying grassy strip land thus has the highest total equalized value—$18.5 million—and the highest possible fiscal impact from putting every rod of our waterside land to grass—a bit over $74,000. The county facing the lowest possible fiscal impact is Douglas County (around Armour and Corsica), with just 53 listed riparian acres whose complete grassification and reclassification would nick local tax assessments by just $377. Statewide, the fiscal impact of total grassification would be $1.24 million, or an average of less than $19,000 per county. The savings per acre for participating landowners statewide would average $5.01 per acre.

I should be careful with those figures and with the word “impact.” The dollar figures assume complete participation by every qualifying landowner on every qualifying acre, which isn’t going to happen. Someone out there will keep planting corn to the water’s edge. The average savings per enrolled acre might actually be higher if the only enrollees are the East River farmers on higher-value land. And “impact” misstates how the proposal works. Like SB 136, the Governor’s plan does not reduce the total levy that each county can set. Brown County, for instance, would not have to lower its budget $74,000 to accommodate complete riparian enrollment. They would have to shift that $74,000 in assessment from 10,000 grassified acres to the other 1.1 million acres in the county, including non-riparian land owned by the farmers taking the grassy buffer strip incentive. In other words, at worst, the Governor’s grassy strip incentive would result in shifting not quite seven cents of property tax to each non-riparian acre in the county. Under that worst-case scenario, a farmer who owns two sections would pay $87 more in property tax.

I have mix reactions about this bill.

The program is 100% voluntary, no one is going to be forced to add grassy strips, or stop using the river to water their cattle. this is a good thing

The Big Sioux River is one of the nastiest rivers around, number 12 or 13 on some nasty river list somewhere. Cleaning up the river would be in everyone’s best interest. I have seen/heard a number of different reports indicating different degrees that grassy strips would help clean up the watershed, everything from it is a feel good measure that really doesn’t do any good to grassy strips make the waters almost pristine; I suspect the truth is somewhere in between.

I would like to add some kind of monitoring process. An annual or bi-annual survey of the watershed showing if the program is really working. If the program is cleaning up the river, great! Let’s keep it going or expand it. If not, let’s scrap it, take what we have learned and try something else.

MC, the folks at the Coteau Area Conservation Districts banquet said grassy strips aren’t just feel-good; they are a great low-tech (no-tech!) response (not a complete solution, but a big help) to water quality.

I’m all for monitoring, especially to gauge the effectiveness of this bill. Send monitors out now, to get baseline data before any new grassy strips are put in, then collect ongoing data in grassed and non-grassed areas to measure changes in water quality. The water conservation districts do some water monitoring; would you like to join me in proposing more funding for such monitoring? (Careful: if you propose a funding mechanism, the SDGOP will send a really nasty postcard about you. ;-) )

Monitoring of the impacts of riparian buffers is underway in a portion of the Skunk Creek watershed in northcentral Minnehaha County. Landowners along a three mile stretch of the creek have implemented buffers comparable to what is supported by the Governor’s proposal. Water quality is being monitored twice each week at four sites to see what the impact is. The East Dakota Water Development District, with support from SD DENR, have been sampling since early in 2014. Results to date have been very encouraging, particularly with regard to bacterial problems. The work is ongoing (our guys go back out tomorrow morning!), but there is a nice summary at:

http://www.sdarws.com/assets/0116-qot-sdarws.pdf

EDWDD is also collecting bi-weekly baseline data on the Big Sioux River, with the hopes of assessing the impact of current and future riparian buffers and other best management practices. (CH – We are mostly using our own funds, but if you can find additional support, go for it!)

There you go, MC! as Mr. Gilbertson points out, we are already collecting some data, which will help us measure the effectiveness of any changes in riparian activities over the coming years. So, would you like to put some Legislative money behind the project, or do you think that the water development district funding is enough to fund the monitoring you have in mind?

Now we’re talking, but, in order for monitoring to be meaningful. it has to be widespread, consistent, generous, temporal random samples that test for not only bacteria and pathogen loading but also full spectrum water chemistry. That is hard to do and it is also very very expensive to do. A single water quality measuring sonde costs in excess of $10,000 just to buy much less operate and calibrate on a weekly basis. Grab sampling is not a good measure of water quality. Everybody that talks monitoring needs to sit down and read through a well designed and practiced monitoring plan such as those used by USGS or NPS.

Having helped design a water quality monitoring system for the NPS Northern Great Plains Region and tested the design in places like the Niobrara River in NE and the Little Missouri in ND, Belle Fourche River in WY I can assure everyone that sample size and broadly distributed, frequent, random sampling is critical to determining if there is an effect from something like this throughout the entire Sioux River from it’s origins to where it dumps into the Missouri. There are far to many variables to sort through! Simply monitoring a few sights on a short stretch of Skunk Creek for a short period of time is not telling and never will be. This has to be a long term, extensive process that produces large data bases of statistically viable sampling in order for anyone to draw conclusions about the affect of buffer strips. One heavy precipitation event in the upper watershed of either Skunk Creek or The Big Sioux is going to skew results and cloud the effect of any conservation effort unless those variables are fully addressed in the monitoring plan. Once a well designed sampling process is implemented; comparative results with baseline information is not statistically meaningful for at least 3 years and preferably 5 or more. When we start installing grass waterways, buffer strips and restoration of permanent vegetative cover on highly erodible soils in all of the Big Sioux Watershed, we might see some positive results after the tributaries and drainages have flushed once or twice. installing strips along side primary stream courses that flow into the Big Sioux is a start but it won’t make much of a dent in solving the pollution problem. Sioux Falls is dealing with contaminants that originate well north of Watertown and buffer strips along the river above Sioux Falls aren’t going to do much good. That’s my prediction. We need to get serious about this and put some serious time, money and effort into it in order to achieve change. The City of Des Moines, Iowa has sued 3 counties above the city due to run off contamination. If they win, we’d best be doing something. Quickly!

We have not experienced our primary run off season as yet and to simply say that buffer strips in a handful of locations on a tributary has a positive effect on water quality is just an abuse of the monitoring process. Long term, extensive sampling over the entire sample frame is the only thing that is going to produce accurate results. Anything less is just grasping at straws.

Can’t rely on grab sampling? Volunteers did that for East Dakota on Lake Herman for a couple years—was that data unreliable? I mean, I don’t want to appropriate money for unreliable testing methods, but does grab sampling really fail to give usable data? Can we make that sampling more rigorous without having to go to the expensive sondes?

Grab sampling can not produce a reliable trend or show spikes in water chemistry anomalies without overwhelming manpower and time expense. There is far to much variability to deal with over time and that includes the human variability. Just because volunteers were allegedly trained and then accumulated a few grab samples of water and sent them off to a lab someplace can not suggest that the samples were taken correctly, equipment wasn’t contaminated and so on ad nauseum. When you’ve got a calibrated sonde taking data that can’t be altered or manipulated in situ, all of that argument goes away. Remember what I said about water quality monitoring taking years. A couple of years data from Lake Herman is just that. A couple of years that can’t deliver a meaningful trend, even if the data was extensive. A

In stream courses in particular, a point or even non point source polluting event can be completely missed by grab samples. A lake is a bit of a different story with grab sampling but it is still inadequate if the samples are not taken frequently, regularly, and at random times of day and locations around the lake. The entire purpose of sampling is to “build a trend” and reduce the number of variables you have to deal with on a regular basis. If you conduct grab sampling in a thorough and ubiquitous manner, it’s going to be more expensive than the sondes. The picture is incomplete with grab samples and they are not defensible either in court or in a political debate.

We have to face reality and quit playing politics with this stuff. A grassy buffer strip 50 feet wide on intermittent tracts adjacent to a major tributary isn’t going to do much of anything to correct non-point source pollutants from entering the stream system from hundreds of thousands of acres of drainage area well above where those strips are. In the prairie pothole region of South Dakota, North Dakota and Minnesota, that may have happened years ago when we had the filtering effect of thousands of acres of wetlands of various types that acted as a nutrient sink and afforded ground water recharge. No more. We’ve plowed out, drained, filled, or channelized more than half of that feature and we’re pouring more fertilizer, chemicals and animal waste on the ground than at any time in history. And now we’re even drain tiling and dumping more water and pollutants into surface water. Grab sampling can’t keep up in an viable way and even if it could, it would take more money, man power, time and effort than developing a good monitoring protocol using good sondes with relevant sensors that can be used to formulate a long term data base and trend. If you want to use grab samples as a method to test consistency and relevance of the sonde data, so much the better. No matter how you look at this, every stream course in this state is compromised, even in the Black Hills and it is going to get worse, simply because the expense and politics of water quality and quantity is a 350 lb, 4.4 speed running back that nobody wants to tackle. I shouldn’t care about this since I’ll be dead and gone long before we have a bigger issue than Michigan or Des Moines, Iowa or other places in the country but it is coming and as Roosevelt said, ” our children won’t vilify us for what we have used but for what we have wasted…… Useable data isn’t the issue. DEFENSIBLE DATA IS…………..

With what frequency do sondes take data, John?

Corey: Like most everything else manufactured with digital technology, Sondes can be programmed to sample water parameters at practically any interval desired. The Sondes I worked with most frequently were programmed to take parameter samples every 15 minutes. The limiting factor, of course, is their memory, how their operating systems are set up and what service and calibration interval is recommended by the manufacturer. Sondes need to be checked regularly to make sure that they are functioning properly and that all parameters are calibrated to exact standards. For my work, we did sonde checks, battery level checks, downloads and calibrations every two weeks unless they were in water that had historical floating debris or constantly shifting substrate or bank configuration. The Niobrara River, as an example, is notorious for it’s sand loading and braiding effects so Sondes needed to be checked a little more frequently to make sure they were not buried or otherwise compromised by hydrologic features, sedimentation and so forth.

USGS has digital technology that downloads and transmits data daily through satellites (or sometimes through wireless technology) to some of their field stations so when employees come to work in the morning, they have the most recent status right there on their computer screen where it can be analyzed, trimmed and added to a data base. USGS in RC has that capability. They can check daily to see if the sonde is functioning normally and if something has gone wrong,

There have been huge advances in technology in recent years that have expanded memory and capabilities well beyond anything we’ve had before and the accuracy is phenomenal. The data bases can be huge so statistical analysis has to be performed at regular intervals otherwise Stat programs like R or SPSS or others simply can’t process the data. Data bases have to be simplified in some cases simply because there is “to much data to deal with.”

I’ve been thinking about this buffer strip proposal a little more and something else comes to mind that nobody is thinking about; or at least hasn’t said anything that I’ve heard.

A while back, I mentioned that USDA has cost shared conservation practices much like this “buffer strip” idea that have been part of the farm bill for at least 30 years. We’ve seen everything from grass waterways, field borders, buffer strips, (it’s what GFP pays for to keep geese out of soybeans) no till and a few other things like swamp buster in robust efforts to protect and conserve water. We have a cumulative problem now much larger than it was before even with those efforts.

If you honestly think about what this might do, it should be obvious that something as simple as a buffer strip could easily turn into a cash cow for the private property owner at the taxpayers and sportsmans expense. It’s happened regularly before and this proposal is just another variation on the same theme; let the taxpayer pay for the damage done by business and industry.

Now before everybody goes on tilt, just think back to last year and the Governors Pheasant Habitat Initiative. (So far it hasn’t raised enough money to make a hill of beans difference in pheasant numbers (and it won’t) but there is little doubt in my mind that that Initiative and the next farm bill are not only going to pay for installation of many of these buffer strips but the public and sportsman are quite honestly going to pay to maintain them. Let’s remember that each Conservation District has the authority to participate in USDA programs that they deem appropriate for their producers and locale. We have a rich history of NGO’s and government bureaus like GFP and SD Dept of Ag, providing cost share funding match with USDA programs in such a way that it doesn’t cost the private producer a dime to implement a conservation practice on their farm or ranch. Right now, DU, as an example, is deeply interested in restoring uplands for duck nesting. PF is actively seeking private acreage for installation of DNC for pheasants, and then we have the Governor’s Funds just for starters. There are other sources of cost share match. Next, let’s consider Thune’s most recent commentary on CRP and the next farm bill. There is no question in my mind that there will be political arm twisting on behalf of Thune and the Governors office to provide federal money to install these types of buffer strip practices in one form or another and keep the funding mechanisms configured to accept sportsmans and NGO money to not only fully fund their installation but also pay to keep them in place for the life of the contract period just like CRP. These so called buffer strips will function much like CRP, the government and the sportsman will pay the bills, and the participating producers will walk into their bank with yet another taxpayer funded subsidy and they won’t have to pay much if anything in taxes. Hows that for “value added income potential.” This sort of thing has been going on for a very long time and to make matters worse; the public will have no access to hunt, fish or anything on that land it is essentially paying to conserve. In some cases, hunters will even pay a fee to access it. Are you starting to understand how these fleecing the taxpayer scams work. It is Thunes specialty. Do all of those possibilities and likelihoods make this “buffer strip” idea a little more palatable to the republican base that hates big government and government over reach but yet devises schemes such as these to use the taxpayer as a source of unearned income for the landed gentry. CRP and similar programs might be a good deal to some and they might be helpful to produce a few pheasants for non-residents to shoot but the real beneficiary are those ag producers that have politicians working on schemes that make the system work for them all the while feeling they are doing something benevolent and beneficial to conserve and promote public assets. A close look at our history in comparison to the conservation of resources should tell all of us that we’re marching backwards in lock step with folks like Thune who understand how to work congress and federal programs. It likely is all about money and not about conserving water……….. but then that is another discussion.

I would agree with Mr. Wrede that the more water quality data available, the better we will be able to assess the condition (good or bad) of our resources. And in an ideal world, we could have a limitless array of constant monitoring devices, along with the necessary support staff to both maintain the network and interpret the data.

Unfortunately, that is not the world we live in. Here in South Dakota, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources maintains a network of about 150 surface water monitoring stations across the state, which are sampled on a monthly or quarterly basis. Additional monitoring conducted by local/regional entities adds somewhat to the data set, especially here in the Big Sioux River basin. East Dakota has committed to ramping up our testing in the past few years, augmenting information collected at SD DENR sites and establishing intermediate sites to fill in gaps. Our hope is to provide a better understanding of both the actual condition of our resources, as well as the impacts of changes in land-use practices (such as riparian buffers and tile drainage). I would prefer to view such an effort as a positive step. It isn’t perfect, but it is clearly better than what preceded it.

If someone can find the resources necessary to create an all encompassing network, that would be great. Until then, I am happy that our efforts can make modest improvements on the system.

Thanks Mr. Gilbertson for your affirmation. In any sampling effort, the largest difficulty is funding and opportunity and I think all of us understand that what ESWDD is trying to do is a best foot forward attempt to get something done in a positive way. I listened to that description three years ago at an IKE’s meeting in Madison and thought that something was finally getting done. I just didn’t feel as though it was enough nor was it well enough supported or done with ubiquitous in application. I still have a lot of questions about DENR’s efforts in all of this as it relates to the Development Districts. Why do we even have WDD’s if the state agency has full responsibility and authority for managing water quality and quantity? We should never accept second rate government stewardship (or the lack thereof) when it comes to assets that belong to all of us. Is ESWDD put in a position of shouldering the responsibilities of State Government and if so, why and what purpose does it serve. I’m not demeaning or bemoaning the Districts, their integrity, or their efforts but rather just questioning whether the routine politics of South Dakota has just established another administrative layer to insulate and protect government from doing the job citizen taxpayers expect. I’ll toss out the most recent “lament” about the WOTUS effort. Would we even have it if the States had taken their responsibilities and duties seriously?

What ESWDD is doing is indeed a positive step and a giant leap ahead of what the West River organization is getting done but that brings me to my main concern, which is getting to little done to late.” Understanding the real world is one thing, accepting it is quite another. I think a lot of us understand the realities; we just don’t believe that they need to be the way they are and have the faith that draconian change is not only possible but essential. Those of us that are deeply concerned about the extent and condition of our natural resources that not only sustain life but also sustain a culture, feel that the political machinery that we’ve had in South Dakota for the last 25 years or more, has ignored these issues or has deliberately exacerbated them to the degree that it is now more expensive, more time consuming, and a great deal more problematic to deal with them. It should not be a continual political argument and partisan debate about what water quality is or isn’t or what will fix it. We know those things already, albeit some of them speak only anecdotally so the question continues to be, why doesn’t leadership take this bull by the horns, find funding mechanisms, send exploitative legislation and policy to file 13 and ramp up our efforts to begin fixing these things before they become too large and two expensive to fix. I’m a firm believer in the axiom; ” an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure”. Right now, the cure is getting too heavy to lift and the political machinery and industry is only paying lip service to it and funding it with even less commitment. Having only minimal data and anecdote is fine and it’s a noble effort but as mentioned, when we’re forced into circumstances of having to use that data to defend conditions or advocate for money or remedy, it can’t stand up to political opposition. All we need to do to see how politics function in these circumstances is look at Flint, Michigan. We should never allow our political machinery to ignore or minimize an environmental issue until it reaches a human and environmental health crisis. But that is what we do. We’ve done it for decades and we just don’t seem to learn anything from our own negligence. What is even worse is we just roll over and play dead when leadership and the political machinery decide that it is the public’s responsibility to fix something that industry itself is solely responsible for. Then we listen to complaints of tax and spend government.

Jay, how much does the current sampling regime cost? How much would it cost to drop a sonde at each of those sampling sites? I’m assuming the cost of sonde-sampling would also include the regular maintenance visits John mentions, which would have to be done by trained staff, not volunteers who just paddle out to make sure the device hasn’t drifted away and is still blinking its little green light.

Last year, analytical costs were right around $50,000, a portion of which is covered by external grant funds. Add to that staff time and travel and I would peg total expenditures at around $80,000.

I have not looked into the costs of the sondes, but I see no reason to doubt Mr. Wrede’s number of $10,000 per unit as a minimum. We are currently conducting regular monitoring at 40 sites in the Big Sioux River basin. Add to that 5 other sites in the Sioux Falls area that the City covers. Sondes for these sites would therefore likely push $500,000. I’d guess that it would take another 10 to 15% of this amount just to cover maintenance and data collection. I don’t know what the defective life-span of these units is, but I would guess 8-10 years might be optimistic. It might be an interesting exercise to look at something in between. Sondes could be installed at critical locations, augmented by “grab samples” at intermediate locations.

A lot would depend on what you are looking for. Our current efforts are based on a mix of targets. We are looking closely (2 samples per week) at a cluster of sites in proximity to an area where riparian buffers have been implemented along Skunk Creek. We are also looking at the river as a whole, monitoring long-term changes in total suspended solids and bacteria. Impairments to the established beneficial uses on the BSR are largely defined by too much of these parameters. Lastly, we are looking at nitrate concentrations in the BSR to assess how we stand compared to all the excitement in Iowa (this is a whole other issue to discuss at another time).

In every case, what we sample for is driven by what we want to know. The sondes typically are not all inclusive. They test for the parameters that you ask for at the time you acquire them. Further, the biggest current impairment to eastern South Dakota waters is elevated bacteria levels. I don’t know if the sondes can test for biologic parameters, so we are looking at field work on top of what the remote devices can gather.

Lastly, we are going to need staff to analyze the data. Our recent efforts have been directed at obtaining data, because there was precious little of it available. This has added to the mix that SD DENR can use to make their biennial water quality assessments (Integrated Report). But all this really does is add more material for a small cluster of scientists to assess (who also have a bunch of other duties). I am looking at either re-directing existing staff or hiring new staff to get more out of this mass of data. My gut tells me that we might be able to remove some water bodies from the impaired waters list if we could spend a little more time going over the data, or redirecting how it is being collected.

Kind of a rambling answer to a specific question, but it is a topic of interest for the District.

Mr. Gilbertson is correct in his assumption that the Sondes won’t necessarily identify specific bacteria loading without supportive sampling and testing. What they will do, if the relevant parameters are installed in the sondes, is provide a good picture of the aquatic chemistry of the stream or water body that is most conducive to bacteria loading. From there, specific sampling and lab testing must be done on a relatively regular basis to measure population densities, distribution and temporal variables.

I tend to think that his estimates of cost may be a bit conservative. The budget for monitoring sites on the Niobrara River in Nebraska along the 60 mile stretch of Recreation River between Valentine and the Phishelville Bridge for one summer season exceeded $150,000 and that didn’t include data analysis to establish a base line. Monitoring of sites on the Little Missouri River in TR, The Belle Fourche at Devils Tower, The Laramie River in WY, the Niobrara River in Agate Fossil Beds and Recreational River for one season (April – October) was over $300,000 without statistical data analysis. There is no question that the process is expensive and much of it is related to travel, per diem, equipment maintenance, calibration and supplies. Any time a Sonde is taken from the water and data downloaded, each of it’s parameters should be cleaned and re-calibrated to national standards. It is easy to install different parameter sensors in the sondes and reprogram them. Depending upon the Sonde manufacturer, I would estimate their shelf life to be something more than 10 years- particularly when most of the manufacturers offer programs of replacement or refurbishing on a regular basis. These things can also be leased from various companies.

To calibrate a sonde that measured DO. turbidity, pH, conductivity, etc. generally took not less than two hours to complete. The calibration standard solutions get used up rather quickly and they aren’t cheap to buy or maintain. Measuring flow rates is also critical to the process and that hasn’t been mentioned yet in the discussion and that equipment isn’t cheap to buy or use.

I guess the point is, monitoring water quality is not cheap, it isn’t easy, and it most certainly isn’t definitive unless it is done extensively to try and eliminate the biases. In my estimation, we’re to the point where the purpose of collecting data is strictly to demonstrate the purity and condition of water to the degree that the data is overwhelming. Defensible data is not something that politicians can argue with and it moves the machinery to action rather than debate. No question that our state programs are inadequate yet struggling mightily to development the answers we need but then I’m not convinced that our leadership wants to know those answers. It’s rather sad to learn that it is necessary to add staff or reprioritize staff’s responsibilities to conduct data analysis that in turn produces answers and recommendations.