The Department of Agriculture (and Natural Resources) announces it has added Dr. Brent Gloy of Agricultural Economic Insights to the roster of speakers at the June 22–23 Governor’s Ag Summit at SDSU, and I end up reading about the rising cost of fertilizer.

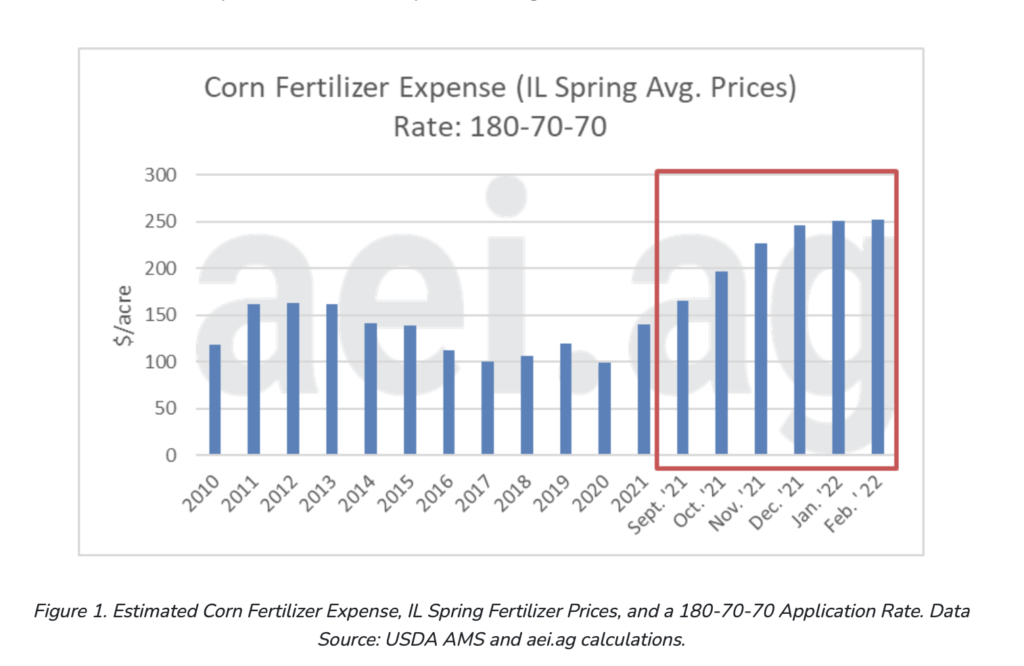

According to Dr. Gloy’s partner in ag-econ David Widmar, the price of fertilizing corn this year will be around $250 an acre, nearly 60% higher than the peak cost ten years ago:

The leveling Widmar charts in February appears not to account for the impacts of sanctions on Russia, which are driving competition for non-Russian sources of fertilizer:

Even before sanctions, fertilizer prices were already high because of supply chain problems and natural disasters shutting down some big plants. Prices were so high that the Family Farm Action Alliance asked the Department of Justice to investigate, and the Iowa attorney general announced his own inquiry.

Then Russia invaded Ukraine. Economic sanctions quickly followed, limiting Russia’s ability to export fertilizer and its raw ingredients. The country’s exports account for 18% of the world potash market, 20% of ammonia sales and 15% of urea. Plus a lot of the natural gas, the most expensive part of making nitrogen fertilizers, comes from Russia.

And while the U.S. doesn’t buy much fertilizer directly from Russia, countries that do are now shopping among America’s suppliers [Jonathan Ahl, “Russian Invasion of Ukraine Has Farmers Paying a Lot More for Fertilizer,” St. Louis Public Radio, 2022.03.14].

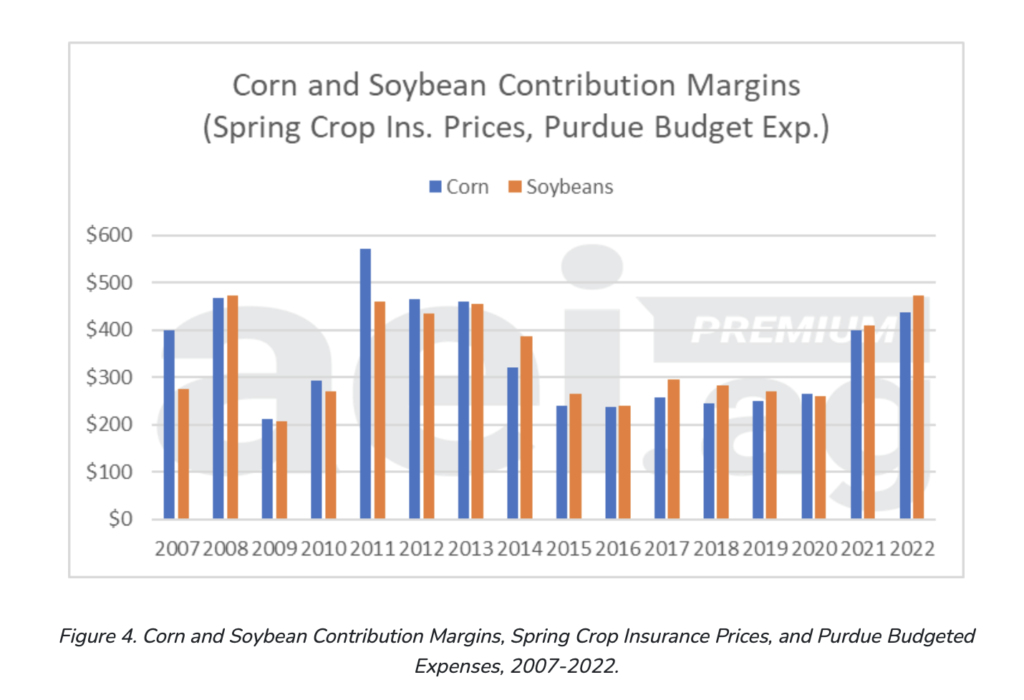

Widmar still projects that corn and soybean prices will produce better “contribution margins”—the amount farmers make after fertilizer costs and other variable expenses—than they’ve seen in a decade:

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and international sanctions against the invader here work in American farmers’ favor by reducing supply and increasing competition for their product:

Wheat, corn and soybean prices are also way up because of sanctions against Russia and the uncertainty of Ukraine’s production and its inability to export. Yet the inclining prices of both fertilizer and grains aren’t guaranteed to offset each other, said Randy Throener.

“Right now the two markets are working together. But they don’t always work together, and that’s the risk that comes this spring and this summer,” said Throener, a partner with BKD, a Springfield, Missouri-based accounting firm that works with farmers [Ahl, 2022.03.14].

Of course, higher prices for farmers mean higher prices for eaters, and the eaters who will feel that bite most sharply are those in poorer countries:

Higher wheat prices will translate into higher food prices for all. But the impact will depend on the farmer share of their food dollar, and the percentage of an individual’s income spent on food.

A significant increase in the price of wheat won’t mean an equally large increase in the price of bread in Canada and the United States. This is because the average farmer’s share for every dollar spent on a loaf of bread is four cents (four per cent). For flour, which is less processed than bread, the farmer’s share is 19 cents (19 per cent).

Overall, the farmer share of the food dollar in the U.S. is approximately 15 per cent, and it’s slightly higher in Canada. The greater degree of value added to the product beyond the farm gate, the lower the farm share.

In contrast, there is a strong correlation between wheat price and bread price in developing countries, where the farmer share of the food dollar can be close to 50 per cent. Wheat price increases will have a significant impact on the price paid for wheat-based products [Alfons Weersink and Michael von Massow, “How the War in Ukraine Will Affect Food Prices,” The Conversation, 2022.03.14].

U.S. farmers may experience higher costs for the Russia-Ukraine war, but the same trade dynamics may boost their sale prices. But the longer war keeps Ukrainians out of their fields and Russian ag products off the global market, the more we may see increases in food insecurity in places like the Middle East and North Africa, which Weersink and von Massow report import most of Ukraine and Russia’s wheat. Our sanctions against Russia may exacerbate those farmers’ costs and global hunger, but we must hope that sanctions hasten an end to Russia’s invasion and a return to normal global flows of ag inputs and outputs.

Because fertilizer is so expensive increased manure applications laced with antimicrobials are sterilizing soils.

Now, because of environmental decimation driven by CAFOs officials with the Lewis & Clark Regional Water System (LCRWS) want to expand output even though water levels in the Missouri River and its basin are at historic lows. Nevertheless, Executive Director of the Lewis & Clark water system Troy Larson thanked the Biden administration for the nearly $22 million appropriation to expand even deeper into Republican territory.

I swear.

I went to Bomgaars store in my olde home town for seed spuds. The 50 pound sag that cost 19 or $20 bucks last year are $27.60 this year. Much higher jump than inflation.

Mike, not surprised. By some data, Russia imports far more than 50% of its potato seed spuds. The Rus will eat fewer spuds in 2022-23.

Russian seed stock for beets is about 5%.

The Rus will soon discover the Putin diet.

https://www.freshplaza.com/article/9398209/situation-with-potato-seeds-in-russia-is-catastrophic/

Bomgaar’s seed spuds come from Minnesota’s Red River Valley.

larry kurtz

Antimicrobials in manure are sterilizing soils?

Quite the opposite according to this study which indicates antimicrobials select for antimicrobial gene resistance which leads to the survival of microbes:

“This study showed that manure application has little effect on soil microbiome but may contribute to the dissemination of specific ARG [antimicrobial gene resistance]s into the environment. Moreover, flumequine residues seem to enhance the emergence of oqxA and qnrS in soil.”

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33199005/

Yeah, no. Not only to livestock antibiotics sterilize soils they kill fungal communities necessary for healthy ecosystems.

https://eos.org/articles/manure-happens-the-environmental-toll-of-livestock-antibiotics

We all watched. The television coverage, just yesterday. That’s on top of everything else that we know and don’t know yet based on what we’ve just been able to see and because we’ve seen it or not doesn’t meant it hasn’t happened.